MP Strikes

introduction

Mike Parr: Foreign Looking strikes deep at the heart of the nation. Here, surrounded by parliament and government bureaucracies that have fashioned our detention centres and offshore processing procedures, the artist installs himself and a vast collection of his work in the National Gallery of Australia.

-

Category

Performance Art, Art History -

Published In

Originally published as Mike Parr: Foreign Looking, Artlink, September 2016. -

Year

September 2016

MP Strikes

Heart of a Nation

Mike Parr, Jackson Pollock the Female, performance, 11 August 2016. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Photo: Zan Wimberley

Mike Parr, Jackson Pollock the Female, performance, 11 August 2016. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Photo: Zan Wimberley

Mike Parr: Foreign Looking strikes deep at the heart of the nation. Here, surrounded by parliament and government bureaucracies that have fashioned our detention centres and offshore processing procedures, the artist installs himself and a vast collection of his work in the National Gallery of Australia. Black holes, anuses, and id spaces collide with the psychosis of a nation that now boasts one of the most appalling human rights reputations ever-imagined in a Western democracy.[1] In this context the exhibition begins with the opening night performance, Jackson Pollock the Female.

A man enters a white-walled gallery space dressed in a long white canvas frock; he sits on a high stool. A make-up artist starts work on his face; assistants stand at attention; photographers and a video operator hover close by the action. The illusion of “performance” is exposed: this is real time, real action, not a scripted narrative. The documentation is incorporated into the event; it is being remediated as it is made. Four big flat screen video monitors are mounted on the wall, feeding close up imagery taken by the roving video camera. There are more screens in the foyer. Hundreds of people from all over Australia are present.

On the back wall of the gallery is the iconic painting Blue Poles (Number 11, 1952) by the American abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock. It was one of the most controversial acquisitions to enter the Gallery’s collection in 1973 when the then director, James Mollison, paid $1.3 million for the picture. The press had a field day.[2]

Pollock, known popularly through the photographs and films of Hans Namuth, has become known as an “action painter” and been used to demonstrate the “performative turn” in twentieth century art. But Pollock is also seen as emblematic of an avant-garde hero in some readings of art history.[3] In others, he is a pawn in the politics of the Cold War where his work was used to symbolise the freedom, equality and fraternity emanating from America while totalitarian regimes were seen to stifle the freedom of artists in the USSR.[4]

Mike Parr is cognisant of the complexities of these art histories and the ideologies that compel them. Performing in front of Pollock is a critique of art history, political ideology, and colonial parochialism; it is also homage to a performative modernist who got caught up in these narratives. More complexly, the performance is a psycho-social analysis of gender in art history. The Bride will recur throughout the exhibition cradling her dysfunctional phallus, represented by the artist’s amputated arm.

Mike Parr, Best Man, 11 April 2006, photograph from closed performance. The Lab Studio, Waterloo, Sydney. Digital manipulation: Felicity Jenkins. Make-up: Chizuko Saito. Photo: Paul Green. Private Collection.

Mike Parr, Best Man, 11 April 2006, photograph from closed performance. The Lab Studio, Waterloo, Sydney. Digital manipulation: Felicity Jenkins. Make-up: Chizuko Saito. Photo: Paul Green. Private Collection.

The figure of the Bride is politically laden. Traditionally given away by the father to another man, she is a piece of property bartered in the patriarchal market place. Furthermore she is promised, dressed in white, as unsoiled goods – a virgin. What does it mean when a male artist takes this figure and its symbolism and parades the mythology as a wounded figure – as art?

In the performance, the Bride before Pollock’s masterpiece is drained. Blood siphoned from veins on the artist’s hand becomes paint for a female artist who performs the action painting that transforms the Bride into a living canvas. The Bride becomes the art object and the property of the museum: a wonky renegade in the father’s house. The audience slowly moves away and into the retrospective exhibition. There are six galleries, a theatre, an archive room/library and the foyer where a collection of the artist’s diaries is on display.

As I move into the foyer I look over my shoulder and see a white video screen. Altered sex words quietly pulse from its electronic void: “outhousesex … overdosex … packing housesex … paraphrasex … parsex …”. A marathon of language sex running 1 hour, 42 minutes and 6 seconds. A Rose by Another Name (Abasex to Zymasex), 1976–2009, is like the first half of a parenthesis. The parenthesis closes with Noh Catalogue in the final gallery where a series of re-mastered political headlines, stencilled over the front pages of The Daily Telegraph, is displayed in table top vitrines: “AFKAN KILLS CAT… MP OVERBOARD … WHITES EAT BLACKS … MP BUGGERS KIDDIES … WARNIE FUCKS POSSUM … MORON VOTES …”[5]

There are other language-based works in the exhibition but these two mark the beginning and the ending and they each give the visitor a pause, a moment to take breath, to lighten up a little. This is a welcome repose since the exhibition itself is visually dense and psychologically taxing. A lifetime of radical performance art, documented in photographs and via film and video, is shown alongside, sculpture, conceptual wall poems written on a typewriter, installations that once housed durational works, paintings and a plethora of large drawings and etchings.

The suites of drawings and etchings are performative in themselves; some demonstrate relations to major performance works while others are performative in the “Pollockian” sense, as analysed by Amelia Jones. Everywhere one imagines the artist’s body engaged with the making of these works. At times notational, at others orchestral, the drawings bring together the mind and body of the artist so that the viewer is able to see more clearly into the psychical processes the artist is working with. At first they create a murmuring through the galleries but this gets noisier as they relate to each other. Eventually, one has the idea that the drawings themselves are a loud visual orchestra, unleashing psyche into the museum.

Parr’s early explorations into the psycho-social are found in the epic cycle Rules and Displacement Activities (1973–83) screening in the front theatre. His intensive investigations into the psychic drives that haunt human relations are shown in three parts: the artist’s relationship with his audience, his investigation of alienation and sensuality and finally the in-depth analysis of his familial relations. The first gallery also shows a series of excerpts from performance work via video projection. This sequence, The montage in space and time, shows work from 1972–2016 spanning early abject and cathartic works through to work which is more overtly political such as Aussie Aussie Aussie Oi Oi Oi, (Democratic Torture) and UnAustralian (all 2003), these are essential viewing for parliamentarians.

Mike Parr, Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi from The Montage in Space and Time, 1972–2016, films, looped play. Private Collection. Cinematographer: Gotaro Uematsu

Mike Parr, Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi from The Montage in Space and Time, 1972–2016, films, looped play. Private Collection. Cinematographer: Gotaro Uematsu

In this room, each of the works relates to the others on screen, spiralling through time, back and forth, and in and out of the body and the artist’s face: in focus, distressed, cut up, stitched. Some are gentle – on one screen we watch as Parr painstakingly creates a house of cards out of his etchings. On an adjacent screen a visual seasickness wells up in the viewer as the one-armed captain, with his hollow shirtsleeve sewn onto his eyebrow, becomes unstable. Playing the psychotic patriot, he completes the salute by aggressively yanking out his stitches, drawing on our empathy and rage.

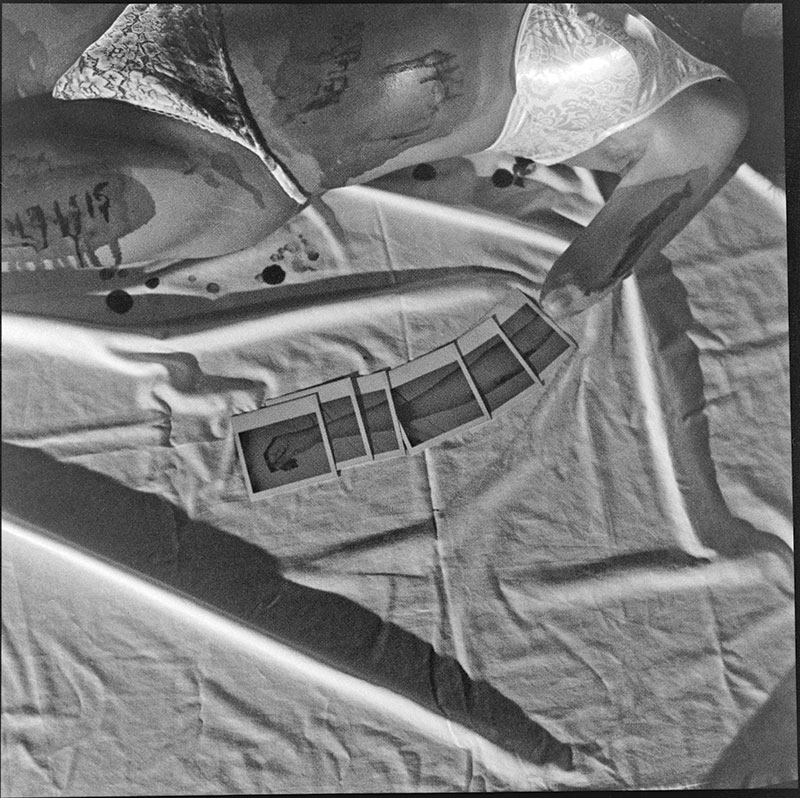

After the screening rooms the viewer encounters The Drawing Boards (2012–16). These have never been shown before – they are notation-like drawings that have been lying around the studio, sometimes for years. They get picked up by the artist and added to. Sometimes he scribbles notes to himself on them, sometimes mundane reminders of phone numbers, other times random words.

.jpg) Mike Parr, Double-sided Drawing Boards, 2012–2015, drawings in mixed media. Collection of Megan Bartlett, Sydney

Mike Parr, Double-sided Drawing Boards, 2012–2015, drawings in mixed media. Collection of Megan Bartlett, Sydney

The result is a kind of palimpsest built up over a period of time. The imagery here is abject, fast, furious. The artist, his father, the landscape recur; faces and body parts are cut, distorted, dismembered. The eyes are often dark, melancholy, blinded. The castrated arm is a protrusion, a stump that recurs as wound and as weapon. In one image the amputation is in the artist’s mouth, which appears as a vagina dentata, and in his other hand he is cradling a head, as if it is a child. Images from performances appear as simple sketches, a bloody chook in the genital region conjures images from Rules and Displacement Activities and the cradled head echoes his Bride portrait Best Man, 11 April 2006 seen elsewhere in the exhibition. Parr says: “I’ve always assumed that the boards weren’t “art” because art doesn’t come into their production. But their mess, their confusion enables me to think about the structure of disorder. When I saw these boards in combination I realised that they were significant … primeval and fundamental … It is the background in particular – notes in relation to the crude drawings and painting – that best complete the boards."[6]

The drawing boards are situated opposite Hitler’s War Wound (2016), a suite of twelve black and white images described as dry point with angle grinder. There is a horse imbedded here but it is abstracted, traumatised, and mashed up amongst faces and body parts. The wounding of the image is violent as the tragedy unfolds: dark and unresolved. These images along with the drawing boards create a channel through which the visitor travels to encounter the rest of the exhibition. The juxtaposition between the deeply personal and the politics of history are enmeshed from the beginning and stressed here in close proximity as the visitor moves on.

In Gallery 2 the Bride persona is dominant but earlier action works are in close proximity, including colour photographs of the infamous Cathartic Action: Social Gestus no. 5 and The Emetics (Primary Vomit): I’m Sick of Art (Red Yellow and Blue), both from 1977. On another wall twelve large black and white photographs show Parr performing one of his instruction works in 1973 Push tacks into your leg until a line of tacks is made up your leg (Wound by Measurement 1). As the eye travels to the opposing wall eight black and white photographs document the 1996 performance Unword (Father, Sister, Jesus, Mother, Marx, Mirror, Arm, Word, God). Here the Bride enacts a bloody rite of passage. She enters the space in an ornate, white dress, then strips down to her bra and underpants. Reclining on a white sheet, she uses a surgeon’s scalpel to cut the words into her flesh and family, church and state become wounds inflicted on the self as other.

Mike Parr, The Emetics (Primary Vomit): I am Sick of Art (Red, Yellow and Blue): Blue 1977, photograph from performance. Watters Gallery, Darlinghurst, Sydney. Private Collection. Photographers: John Delacour, Felizitas Stefanitsch

Mike Parr, The Emetics (Primary Vomit): I am Sick of Art (Red, Yellow and Blue): Blue 1977, photograph from performance. Watters Gallery, Darlinghurst, Sydney. Private Collection. Photographers: John Delacour, Felizitas Stefanitsch

Mike Parr, Cathartic Action, Social Gestus, No. 5 (the "Armchop"), 1977, photograph from performance, Sculpture Centre, The Rocks, Sydney. Private Collection. Photo: John Delacour

Mike Parr, Cathartic Action, Social Gestus, No. 5 (the "Armchop"), 1977, photograph from performance, Sculpture Centre, The Rocks, Sydney. Private Collection. Photo: John Delacour

Mike Parr, Unword (Father, Sister, Jesus, Mother, Marx, Mirror, Arm, Word, God), 1996, photographs from performance, Fine Arts Department, University of Western Australia, Perth. Private Collection. Photo: Peter Mudie

Mike Parr, Unword (Father, Sister, Jesus, Mother, Marx, Mirror, Arm, Word, God), 1996, photographs from performance, Fine Arts Department, University of Western Australia, Perth. Private Collection. Photo: Peter Mudie

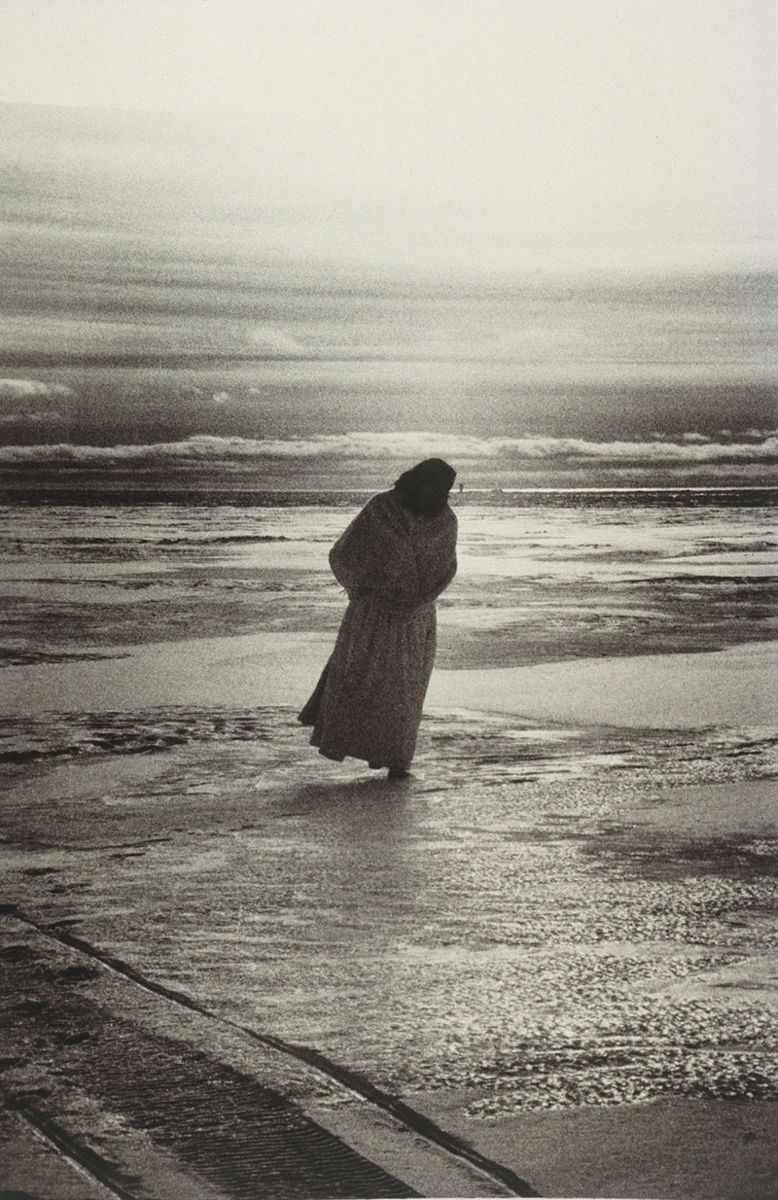

There are multiple bride performances documented in this gallery together with a life-like cast bride " sculpture. The End of Nature (1998) shows an aged bride trudging through the snow at the Baltic Sea. She wears a flimsy wrap and looks haggard and beaten by the elements, she walks until she collapses from exhaustion. In a more light-hearted appearance Barbara Cleveland Eats An Apple, commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and BC Institute in 2016 Parr pays homage to Cleveland, the female performance artist forgotten in art history and rediscovered by the Institute. As indicated earlier, the Bride works are complex constructions because of the gender displacement and re-enactment. Parr says: “The Bride is a constructed image, a kind of screen or cosmetic overlay. The repetitive duration of the Bride performances wears the image down. I am interested in disrupting the symbolic order. The breaking of the image remains very important to me”.[6]

Here feminine dress is used as a performative tool and aligns with Judith Butler’s analysis of performative sexualities.[7] Parr is not simply performing otherwise or becoming feminine; there is no desire to pass as a woman. Rather he uses the gendered performance to indicate the made-up, artificial, cosmetic rendition of identity itself, projecting the Bride as a screen. His attempt to break the image, to wear it down is a political act but one which gets under the skin, it will touch and incite people in different ways.

In Gallery 3 the intensity of the psychological interrogation of self and identity is made explicate for the viewer. It is difficult to escape the torment here but there are moments of tenderness. In one of the 26 Untitled Self Portraits (1981–96) the artist is seen with a tiny penis that has grown in the armpit of his amputation, it hovers above a female breast that has grown from the same muscle group. His head is too large for his body, his adult face melancholy, his mouth and gaze downcast, as if looking with momentary disgust or disbelief at the genitals resting in his lap. It’s a gentle image, a vulnerable displacement and a corporeal extension of a deep psyche.

In front of this suite of portraits a band of sixteen Bronze Liars (1996) stage a kind of static performance on museum plinths. They appear as the decapitated heads of dysfunctional warriors, wounded by the partially blinded artist in the re-modelling process. The sculptures are another example of the artist pushing the image to its destruction, in this instance by colliding conscious and unconscious making. Overseeing the Liars is a pair of monumental drawings, which includes Son of Jesus (1993), where a crucified figure is drawn in red ink over a series of partially erased black and white sketches. His right arm is amputated in the image, representing a mirror image of Parr’s physiology. His left arm is entire and outstretched, his hand pierced by a thick red wedge. The wedge shape recurs in The Bridge(Voiceless) (1992), which is installed along the length of the gallery at head height. A series of triangular wedges made out of wax sit on top of a burnt piece of timber. It was initially a participatory installation where the audience was invited to put their heads into the hollow spaces – to literally bury their heads (ears, eyes and mouths) into a hollow void. In Canberra there was no invitation to participate but a small video documented one of the earlier events to demonstrate the work in action.

Mike Parr, Bronze Liars (Minus 1 to Minus 16), 1996, Sydney, bronze and beeswax sculptures, installation view, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Mike Parr, Bronze Liars (Minus 1 to Minus 16), 1996, Sydney, bronze and beeswax sculptures, installation view, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

.jpg) Mike Parr, Son of Jesus, 1993, Sydney, drawings in pen and ink, brush and ink, pencil and pastel. Collection National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Mike Parr, Son of Jesus, 1993, Sydney, drawings in pen and ink, brush and ink, pencil and pastel. Collection National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

The exhibition continues with three more galleries, each as compelling as the other. As the viewer leaves Gallery 3 she moves into a sparse room to encounter The Golden Age, a large triptych of black ink drawings made with various tools, including an angle grinder. The equipment seems bizarrely appropriate for the task as Parr presents three intense analyses of masculinity in his family from childhood to adulthood. Subtitled Choking, Field Day, Extinction the imagery is a mixture of resolved portraits, where faces are clear, and a frantic kind of haptic visual gesturing where an infant’s body appears to be trapped under a black tide.

To get to the final gallery, the visitor passes through another corridor space where Parr’s distorted face is shown photographed through his mother’s glassware (1982). This work relates back to the screening room and the final movement in Rules and Displacement Activities where the artist filmed his family underwater. On the opposing wall is a fairly grotesque and abstracted homage to his father.

At the end of the exhibition Parr presents the Noh Catalogue in the centre of the room and surrounds it with massive paintings made by painting over etchings of his face. The paintings are titled Foreign Looking (2013–15) and their actualisation took over 70 hours. The endurance event is documented on video with a soundtrack of a Chinese choir signing The East is Red and The Internationale. Parr relates the action of painting over his suite of self-portrait etchings to the earlier performance Cathartic Action: Social Gestus No. 5 where he re-enacted the trauma of losing his arm by chopping off a prosthesis filled with blood and offal. The artist says: “I have a funny relationship to time … I operate in a kind of spiral”. This is certainly apparent in the exhibition at the NGA, not only does the floor plan entice a spiral movement for the viewer through the space, but each gallery is installed so that the works speak to each other across and through time. It is a magnificent show and well worth a stopover in Canberra.

Mike Parr, The End of Nature, performance, Baltic Sea, Umeå, Sweden, 18 February 1998, film, looped play. Photo: Felizitas Parr

Mike Parr, The End of Nature, performance, Baltic Sea, Umeå, Sweden, 18 February 1998, film, looped play. Photo: Felizitas Parr

Footnotes

-

Writing about his Black Box installations Mike Parr said: “Id Spaces, Black Holes, Bermuda Triangles, autistic dilemmas, linguistic double binds, paranoid projections, anuses, throats … more and more the installations underline an absence in order to reveal a presence (a strategic double negative)”, as quoted in Presence and Absence: Survey of Contemporary Australian Art No. 1, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 1983, p. 36.

-

“The painting was reviled at the time as the work of ‘barefoot drunks’ and its purchase seen as a symbol of Whitlam-era financial excess. In retrospect, it was one of the nation's most savvy art purchases. Worth more than $40 million, it is now the pride of the National Gallery of Australia's collection.” See Joyce Morgan, ‘Gough! Splutter! Museum's blue poles cause a whole new row’, The Age, December 12, 2003. Accessed 24 August 2016 at: The Age, December 12, 2003.

-

Harold Rosenberg first used the term action painting in 1952 after he had seen Namuth’s photographs. See Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Jackson Pollock, Painting and the Myth of Photography’, in Orton and Pollock (eds.), Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed, Manchester University Press, 1996, pp. 165–66. Also Amelia Jones, ‘“The Pollockian Performative” and the Revision of the Modernist Subject’, in Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing the Subject, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis and London, 1988, pp. 53–102.

-

For interpretations of Pollock in art history see Francis Francina (ed.), Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, Routledge: London and New York, 2000 (first published Harper and Row, 1985).

-

Amelia Jones, op. cit.

-

Mike Parr, edited extracts from email exchanges with the curators published in the untitled exhibition brochure, National Gallery of Australia, 2016.

-

Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex, New York and London: Routledge, 1993.