Art

& Feminism

introduction

The state of the art world and of feminism in the twenty-first century ushers in different ways of doing political activism, cultural work and theory. The intergenerational aspects of feminism and how this has been enacted in the visual arts in recent years represents a refreshing change from earlier perceptions of waves of feminist theory that tended to privilege the new.

-

Category

Art History, Feminism -

Published In

This Article first appeared in Artlink, Positioning Feminism, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2017, pp. 8-21. -

Year

2017

Art and Feminism

Generations and Practice

It is increasingly clear that there are no topics or phenomena to which a feminist analysis is not relevant—at which point it is useful to consider feminist theory ... as a set of techniques, rather than as a fixed set of positions or models. [1]

The state of the art world and of feminism in the twenty-first century ushers in different ways of doing political activism, cultural work and theory. The intergenerational aspects of feminism and how this has been enacted in the visual arts in recent years represents a refreshing change from earlier perceptions of waves of feminist theory that tended to privilege the new. The visual metaphor of the new wave dashing the old against the shore appears to replicate traditional paradigms in what some have called either an Electra or an Oedipal contestation where the new generation kills the old feminist mother in order to please the father (the academy).[2]

More recent debate around the generations seeks to appreciate feminist values and achievements across the generations. There are several things that may have influenced this change of approach that is characterised by intergenerational research. In the art world process work is once again being acclaimed as conceptual, politically engaged and experimental. The contemporary art market, reflecting the experience economy, is finding ways for clients to buy and collect process-based works. Those more adventurous can opt to participate in the works such as Marina Abramović’s residency for John Kaldor and David Walsh (MONA) in 2015 where people could wear noise-cancelling headphones and silently count rice and lentils (black and white grains) in a calm clean installation, or get tucked into small camp beds in a former warehouse at Pier 2/3 in Sydney.[3]

On a more scholarly edge feminism has become an academic organism and is debating some of the most profound issues of our times—the state of a depleted planet, the sentience of all things biological and geological, the state of gender difference in a poly-gendered world, the psycho-political-historical position of the other in a world ravaged by war—and the ways in which this plays out in women’s lives and on their bodies. Feminism is now more intersectional as it reaches beyond its white middle class privilege and others, more fully engaged with race, ethnicity and non‑binary positions take feminism on.

The intersection between experimental practice and theory in association with feminism is evident in recent lens-based, performance and participatory art. After postmodernism it is impossible to separate representations of the female body from a feminist interpretation, and even before this feminism was a practice as well as a multifarious socio-political platform. Some would say (and once said) that feminism is praxis. Others might say that doing feminism is a way of being in relation to the world. This is certainly the case for object-orientated ontologists and new materialists who critique the dominance of the anthropocentric and find sentience beyond the human.

Jeff Wall, Picture For Women, 1979, transparency in lightbox. Courtesy the artist

In terms of feminism and the arts it is important to understand that much contemporary visual art practice by male and female artists since the 1970s is informed by or reacts to feminism. Both Jeff Wall’s Picture For Women (1979) and Victor Burgin’s Office At Night (1985) analyse the gaze within a feminist discourse. Many of the debates underlining the postmodern period centred around issues of representation, where race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality entered new arenas of critical discourse. Fiona Foley, Destiny Deacon and Tracey Moffatt are strong intersectional protagonists, as are Elizabeth Gertsakis, Nasim Nasr, Eugenia Raskopoulos and Cigdem Aydemir.

The gaze informed the works of thousands of artists as gender stereotypes were unpicked, surveillance was politicised and personalised, and issues around desire were seriously and playfully espoused through art (Caroline Williams, Anne Ferran, Merilyn Fairskye, Pat Brassington). The body as a gendered body was centre stage not only in performance art, photography and video but also in more conventional media such as painting and printmaking. The body as representation ranged over critical positions as theories of the abject, trauma, affect and analyses of the psycho-social subject jostled with a tidal wave of identity politics as postmodernism engaged with pluralism. The individual was decentred, cut up, tortured, remembered, deconstructed, forgotten and sabotaged in a multitude of ways (Linda Sproul, Fiona Macdonald).

When discourse around the postmodern started to dry up we entered into a new world of the post-human and the post-feminist. Donna Harraway, at the forefront of post-human feminism, famously claimed in 1987 that she would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.[4] New materialism, which arises as a variety of responses to the ecological crisis, the perceived neglect of nature/biology in feminist scholarship and the new advances in quantum physics, jostled with the decentred technologically and biologically enhanced post-human and claimed that the human being is part of a much wider relation with other species and the ecological terrain that s/he inhabits. Like postmodernism, this period is fraught by its pluralistic approach and so various positions vie for attention.

It is evident the sciences and the humanities and creative arts are often at odds in the post-human world. Both believe that matter really matters now, but some avenues in the radical techno-biological sciences foresee a new “singularity” where the human becomes enhanced by bio-technology: a future without disease, where immortality is a possibility.[5] In contrast the humanities are concerned about the ethics involved in this brave new world and how power is bound to corrupt what sounds like a utopia. Who will be able to afford to be enhanced? Who will be willing? Will people passively submit while their biological self is altered/enhanced?

Feminist physicist Karen Barad, who champions matter and the intelligence of nature, compels us to think seriously about our place in the world. What is clear from all of this is that we have moved forward with a backward glance to the ecological concerns of previous generations. Barad, in an often-quoted passage, argues that: “The linguistic turn, the semiotic turn, the interpretative turn, the cultural turn: it seems that at every turn lately every ‘thing’—even materiality—is turned into a matter of language or some other form of cultural representation ... There is an important sense in which the only thing that doesn’t seem to matter anymore is matter.”[6]

This return to thinking seriously about matter, nature and biology, through quantum physics is a welcome pause for many people who felt stifled by the linguistic turns of the last forty years. For feminism, it effectively re-opens dialogues around sexual difference that had been closed down by structuralist/post-structuralist theory which prioritised language and representation. In short it offers a salve against decades of debate within feminism over the nature/culture split in relation to gender identity, and the ensuing criticism waged against the “essentialists” who celebrated sexual difference (an essential female and/or feminine experience and identity).

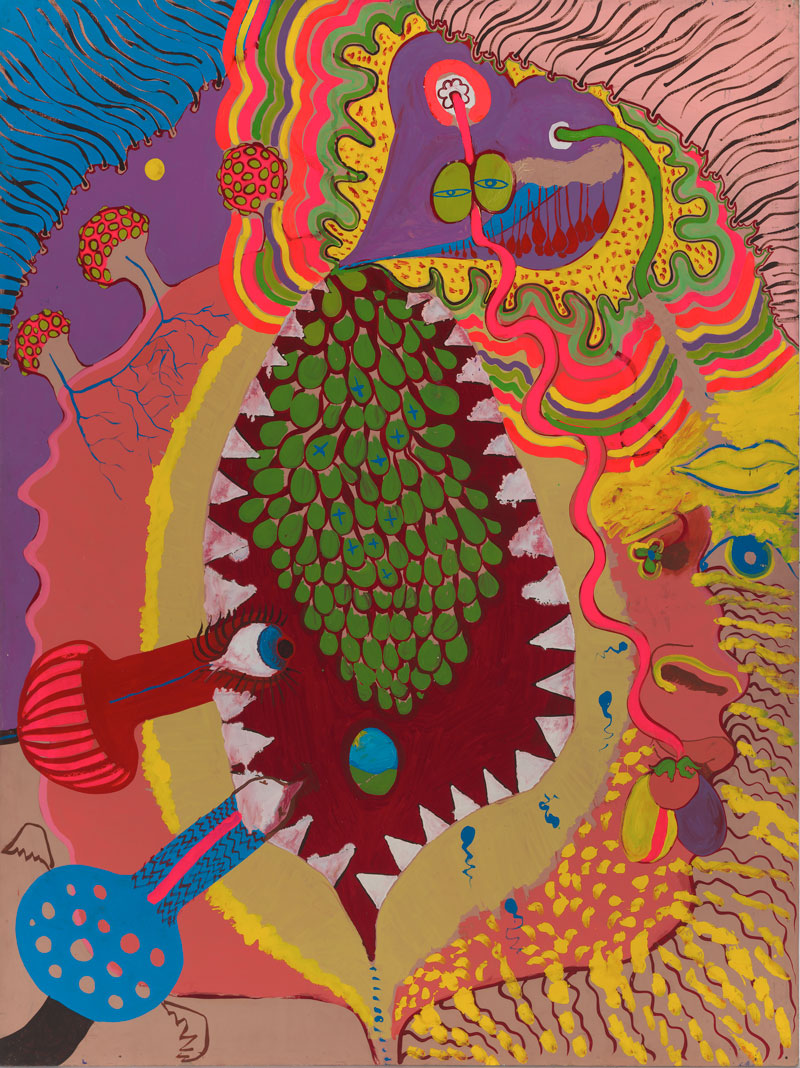

In Australia the work that often signifies the power of the (essential) female body is a painting, Vag Dens by Vivienne Binns, first shown at Watters Gallery in 1967. Binns was closely associated with Mike Brown and the alternative pop art scene in Sydney that celebrated sexual liberation, Eastern spirituality and psychedelic culture. It was from this culture that Vag Dens emerged. It was a radical statement and one that was lampooned by critics, causing Binns to seek out a more compatible feminist culture.[7] Deborah Clark argues that “Binns anticipated a key aspect of feminist art practice internationally with this adoption of essential imagery.”[8]

Vivienne Binns, Vag Dens, 1967, synthetic polymer paint and enamel on composition board. Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra ©Vivienne Binns/Licensed by Viscopy 2017

The focus on woman’s nature, her body and personal experience was important to feminism in the late 1960s and 1970s. This certainly had affiliations with the counterculture movement, sexual liberation, and a return to nature. But running parallel with this was the New Left and various forms of Marxism, Maoism, Trotskyism, socialism, anarchy and feminism with any mixture between them in varying degrees.

Simone de Beauvoir first claimed woman is not born but rather becomes female and prefigured the idea that we are subjects who are already written by patriarchy, capitalism/the family, church and state (to paraphrase Louis Althusser).[9] This subsequently underpins all structural analysis from the male gaze of Laura Mulvey to Judith Butler’s theory of performative sexuality.[10] Although some thought that Butler may have offered an inkling of agency through gender performativity, according to Barad they were not paying enough attention to her ontological thesis. Judith Butler may try to bridge the nature/culture binary with performative theory, but instead she reinstates it claiming in her own words that matter (nature) is already “fully sedimented with discourses on sex and sexuality that prefigure and constrain the uses to which that term can be put.”[11]

In art the performative became a conjunctive term as in performative photography where it was used to describe what has also been termed directorial photography (Gregory Crewdson, Jeff Wall). Performative photography is still widely used, perhaps because it signals the relationship between this mode of photography and performance art, especially when artists such as Cindy Sherman and Julie Rrap photograph themselves.[12] On a pedestrian level Butler’s performative was often highjacked and its philosophical constructivist meaning lost but artists have played with the ambiguity apparent between the performative and constructivist (Rosemary Laing, Polixeni Papapetrou, Julie Rrap). Tracey Moffatt’s engagement with Aboriginal experience, history, postcolonial and feminist thinking presents some of the most important work of its time and she often embraces a performative methodology, using it to present multiple viewpoints and interceptions.

.jpg)

Julie Rrap, Disclosures, 1982 (detail), black and white archival prints, fishing line, cibachrome prints on aluminium. Courtesy the artist. © Julie Rrap/ Licensed by Viscopy, 2017

It appears that theoretically at least we are in a more open dialogue and relativity and ambiguity may be being valued more than dogmatic positions. Amidst all of these turns the one constant for feminism oscillates around arguments about sexual difference and what have become known as the difference debates. Several events converge in the twenty-first century to focus attention on these debates and they play out in the academy with the shift from women’s studies (established in the 1970s) to gender studies and then to queer studies over a period of three decades. As these changes occurred, woman as the subject of critical thinking gradually moved further away from core intellectual business, and in some cases simply disappeared as the subject of investigation in the academy.[13]

The difference debates also play out in the Western world (in particular) through advancements in medical science that make gender reassignment a real possibility. One can be born male or female and change one’s gender through hormone replacement therapy and genital surgery. This is liberating for those who feel trapped in the wrong sexual identity because of their physiognomy, but it causes interesting and complex questions for feminism. What is it to claim identity as a woman based on biology in a Western world in which gender reassignment is a reality? What are the rights of the woman who was not born female? How does transgender identity support and/or depend upon Simone de Beauvoir’s “woman is not born” pronouncement that underpinned so much feminist scholarship? How is trans‑sexuality figured in new materialism that reasserts the importance of nature and matter?

These shifts question assumptions about nature, biology and subjectivity. For feminism, they again raise the question: what is it to be female and/or to become a woman? Where does this leave the difference debates in feminist scholarship? Being the wrong sort of woman, not looking like the ideal woman in the visual imaginary of patriarchy, is something that has plagued women for centuries and been the subject of a range of art.[14] Maria Kozic upset talkback radio hosts and their callers as well as feminist critics with her billboards Maria Kozic is Bitch in Melbourne and Sydney for the Biennale of Sydney in 1990. The audience was divided about how the artist represented her own body, was it demeaning to women or empowering? Deborah Kelly appropriated the work for the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras with her queer version Mahalia Jones Is Butch in 2009.

Deborah Kelly, Big Butch Billboard, In Homage to Maria Kozic, 2009, mobile billboard. © Deborah Louise Kelly/Licensed by Viscopy, 2017

In the difference debates, feminism has been divided along a binary axis for some time and the transgender issue perforates this divide. In the binary, the constructivists and many activists campaigned for sameness: women should have equal rights, be equal to men, be allowed the freedom to operate in the world in the same way as men. They were as good as men. Some would argue they were better: good enough to have two jobs at the same time—producer and reproducer, corporate citizen and nurturing mother. Those deemed essentialists wanted to nurture and celebrate women’s difference from men. Woman should be seen as a powerful being in her own right as nurturer, mother, caregiver. But, as many socialists and constructivists pointed out, this was apt to fall into the role that patriarchy had already assigned to women.

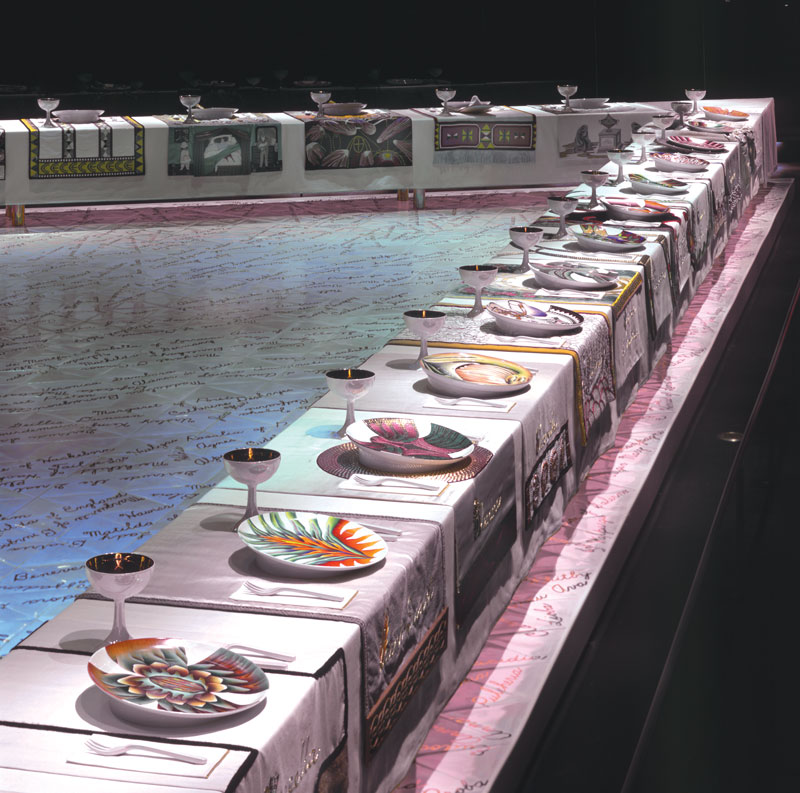

In feminist art, this all plays out in the comparison between two key works of art: Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–79), first exhibited in 1979, in Australia in 1988; and Mary Kelly’s Post Partum Document (1973–79, first iteration shown in 1976, in Australia in 1982). Chicago (and a host of volunteers) used embroidery and ceramics (craft skills) to create thirty‑nine place settings for mythical and historical women positioned around a grand dining table. Disregarding the fact that Chicago’s workplace relations were oppressive and many volunteer craftswomen were exploited, The Dinner Party is still a significant work for art history.[15] Post Partum Document in contrast is deeply personal, political and theoretical. Mary Kelly uses the tools of the conceptual artist and creates a durational work that documents the first six years of her son’s life and the relationship she develops with him as a woman and a mother. Drawing heavily on Lacanian psychoanalytic theory Kelly documents the child’s coming into being through language. These two works demonstrate the difference between feminist approaches and how they were developing concurrently.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79 ceramic, porcelain, textile Installation view, Brooklyn Museum Photo courtesy Judy Chicago / Art Resource, NY © Judy Chicago/ARS. Licensed by Viscopy, 2017

The constructivist position was dominant in American and British academic feminism but not as obvious in art practice until the 1980s. In Europe the idea of a feminine writing pioneered by Hélène Cixous and Monique Wittig had considerable traction in France, but was criticised by the Anglo-American postmodernists for prioritising an avant-garde approach, one deemed to prioritise humanist agency. Julia Kristeva who held up the works of male avant-gardists was also criticised, but her theory of the abject was popular with artists, curators and art critics.[16] On a philosophical and psychoanalytic level the work of Luce Irigaray has attempted to chart a new feminine ontology—a divine sexual being—and a new way of being together that has attracted new materialists and feminist relational artists.[17] Countering the social constructivists Irigaray asks: “Equal to whom?”[18] Why would woman want to be equal to men? Why would she want to be anything like men? Why wouldn’t she want to acclaim her difference?

Feminist theory creates a complex philosophical and political discourse in the twenty-first century by building on, examining, extending and re-positioning feminist discourses over the last hundred years. Feminism has developed a strong voice in academia. Women’s art across the globe is representing issue-based and experiential work. The art world and to a lesser extent arts publishing reflects this. FEMMO™, Virginia Fraser and Elvis Richardson, collaborate to produce mock magazine covers of Australian women artists. Inhabiting the space of the wide-eyed laughing medusa, to paraphrase Hélène Cixous, they reflect a groundswell of activism that critiques art-world hierarchies, mainstream ideologies and market-dominated male privilege. But regardless of such provocative suggestions and an avalanche of critical theory that has infiltrated almost every scholarly discipline, real change is slow and women’s lives are still impacted by inequality. The suggestion that we are in a post-feminist world can only be voiced from a position of privilege, one that either has no concern for human rights or excludes women and children from humanity.

Feminist art is a broad topic in the twenty-first century. We can talk about art in terms of its feminist content and interpretation; through its themes, its standpoint, what it represents and the issues it focuses on. We can also look to a feminist practice and see this in process rather than in content, or as both. Feminism is no longer gender-specific: we can certainly see feminist impact on and interpretation within work by male artists. Feminist art history is an even bigger field as it addresses all art. Some of the best feminist scholarship in the arts concerns the canon of art history and the works of great male artists.[19] From a feminist art history perspective, we can also talk about the medium of the work, its approach, its style, and cast some opinions about a feminine aesthetic.

The medium (the matter of art) has been on the critical agenda again over the last twenty years. After the hiatus associated with the decline of Clement Greenberg, it was revived in the late 1990s as artists and scholars critiqued and/or endorsed what Rosalind Krauss termed the post-medium condition.[20] Krauss believed that the onslaught of installation art was destroying the integrity of art.[21] Much like Greenberg before her, Krauss argued that artists needed to return to the essential qualities of the medium not dissipate their energies with the more performative/theatrical aspects of installation, video, performance and relational art. More recently those convinced by the sentience of things beyond the animal kingdom, the new materialists and the object-orientated ontologists, advocate that art has its own being (it thinks and feels): the medium talks back.

Despite the problems inherent in the history and critique of the medium in art, women artists have been drawn to abstraction.[22] This is evident in painting, where women were active through the hard-edge and colour field schools, and in sculpture and installation from the 1970s. Women persisted with abstraction throughout the postmodern period. Elizabeth Gower’s collages made up of thousands of tiny images cut from advertising brochures and magazines presents abstraction with ironic critique. Rosalie Gascoigne’s sculptural installations from materials found in the landscape or urban areas is a more conventional Zen poetic with its roots in Ikebana flower arrangement and arte-povera. A younger generation of artists, coming to prominence in the 1990s, that continues to subvert formalist abstraction through alternative material and sub-cultural references, includes Elizabeth Pulie and Kathy Temin.

Rosalie Gascoigne, Down To The Silver Sea, 1977, 1982, wooden box, galvanised iron, cotton flour bag, photographic reproduction, plastic doll leg. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Gift of Peter Fay 2002 ©Rosalie Gascione/Licensed by Viscopy, 2017

There are many ways to approach feminism and the feminine in art but for the rest of this paper I want to concentrate on the resurgence of a process-orientated methodology that has its roots in the small group processes of the early women’s liberation movement. After decades of representational art about women and their experiences, some artists are turning to a practice of doing feminism. Group structures and participatory practices associated with women‑only gatherings are being revisited as a way of making art.

These practices first emerged in the 1970s in dialogical performance and participatory community art. Mothers’ Memories/Others’ Memories (1979–81), a long-term project by Vivienne Binns, working with women in the suburb of Blacktown in Sydney, is one of the most notable examples.[23] The community-focused, event-based, works of Anne Graham are also highly significant in terms of establishing precursors for relational aesthetics, which was proclaimed as a new direction in the art of the 1990s by the French curator Nicholas Bourriaud.[24]

Many artists working in the 1970s, both male and female, sought to find avenues to bridge the gap between art and life, to make art more meaningful in communities and to create work that had a broader resonance across different sectors of society. In short, artists wanted to make art outside the gallery/museum and market structures that they found hierarchical and constricting. Banner making, community murals, street theatre, postcard and poster making were all practices that became embedded in life and work. For a period of time, the Australia Council for the Arts, through its Community Arts Board funded quite a lot of this activity, and in association with the Trade Union Movement, it funded the Art and Working Life Program that placed artists in work environments. Much of this work came under heavy criticism with the onslaught of postmodern theory in the late 1980s, primarily because of the Marxist legacy of such programs that were seen to preserve a humanist agency.[25] These early activist platforms and models for the arts have yet to be thoroughly researched. This is unfortunate because there has been a rekindled interest in participatory practice through relational aesthetics that would benefit from more socio‑historical contextualisation.

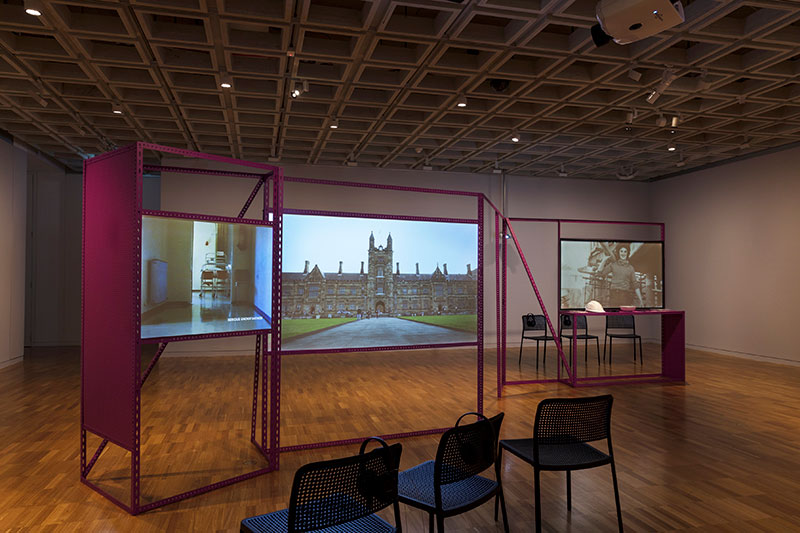

Alex Martinis Roe, It Was About Opening The Very Notion That There Was A Particular Perspective, 2017, Installation view. Courtesy and © the artist and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Writing about the new relational and dialogical practices of the late 1990s, Nicholas Bourriaud insisted that the open-ended studio approaches he was seeing in practice were not related to a 1960s paradigm.[26] Instead he argued that they were collaborative communities. Claire Bishop is not convinced and observes that such practices facilitate a neo-liberal agenda evincing a move from a goods- to a service-based economy.[27] This axis of experimental practice and the experience economy is troubling but predictable. It is part of a general co-optation of all ideas and things to economic ends. Feminist dialogical works, which are often distinguished by the small group processes and resistance to spectacle, may disinterest potential economies for a time.

The work of Italian feminism and its history is being discussed by a younger generation interested in new political models of participatory art.[28] Alex Martinis Roe has produced a series of films and participatory events in Europe and Australia that are based on extensive historical research into group practices amongst women. It was the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective’s concept of affidamento, entrustment between women, that first inspired the artist to re-create some of the key meetings and personal‑political gatherings of an earlier European women’s movement. To ensure the integrity of the process Martinis Roe wanted to create ways of telling these stories about doing feminism modelled on those historical practices. In this way, small group processes were used as “a springboard to adapt those practices to the contexts, needs, desires and competences of the younger generations.”[29]

The project To Become Two (2014–16) comprises a series of six films plus workshops and events designed for each context. For her contribution to The National 2017: New Australian Art, Martinis Roe spent four months speaking with women associated with Feminist Film Workers, the Sydney Women’s Film Group, the Sydney Filmmakers Co‑operative and those who were involved with General Philosophy at Sydney University in the 1970s and early 1980s and the Working Papers Collective.[30] The film title It Was About Opening The Very Notion That There Was A Particular Perspective is a quote from the film where one of the narrators (Vicki Kirby) is talking about gender studies at Sydney University and the popularity of Elizabeth Grosz’s lectures and Moira Gaten’s Irigaray Reading Group.

The film was shown as an installation at the Art Gallery of NSW alongside excerpts from Helen Grace’s Serious Undertakings (1983), Margo Nash’s Shadow Picnic (1989) and Pat Fiske’s Rocking The Foundations (1986)—snippets of which were edited into Martinis Roe’s film, which was narrated by the feminist filmmakers. The exhibition space was muted at times to allow for a program of talks (where the narrators spoke about their political practice) and the Salon where a group of women, some involved in the films, and younger artists, writers, academics, designers and curators responded with propositions that had been developed collaboratively in the workshops. The day I participated as part of the outer circle, there were about ten people on the inner circle who were presenting propositions in response to “opening the very notion that there was a particular perspective.”

Kate Just, HOPE walk Leeds, 2014, type C digital print, Courtesy the artist

.jpg)

Kate Just, SAFE walk Melbourne, 2014, type C digital print, Courtesy the artist

The most interesting part came when a self‑acclaimed psycho‑therapist and shaman interjected from the outer circle saying that she found the discussion overly academic and that for her feminism is embodied and it is important to celebrate the divine nature of the feminine body rather than getting tied up in the language of reason. Two of the women in the inner circle responded: Margo Nash embraced the idea and spoke about love, Vikki Kirby defended intellectual and artistic inquiry. It was an awkward and real moment. The psycho‑therapist wasn’t impressed and left shortly afterwards. In this exchange feminism’s recent history somersaulted across the room as the binary divide between the soft warm body and the cold hard mind was named. The process facilitated by Martinis Roe allowed this to happen providing a holding space for the interaction.

In the women’s liberation movement small “consciousness raising groups” were coordinated to allow women a space for discussion about their roles in the family, the workplace and society, and the issues and discriminations they faced. This method of practising feminism was criticised by postmodernists for prioritising women’s experience (and their humanist agency) but it has arisen again through participatory art and craft practices amongst women. This can be seen on a grass roots level through the rise of craftivism that builds on a history of feminist practices at women’s peace camps and activist sites.[31] The Knitting Nanas use their craftwork as an anchoring point for political activism in their persistent campaigns against the mining of coal seam gas in Australia.[32]

Kate Just uses craft to create sculpture and brings community knitters together around issues that affect women. KNIT HOPE (2013) and KNIT SAFE (2014) are large‑scale banners that are used in independent processions and at protest marches concerned with violence against women and children. Margaret and Christine Wertheim’s Crochet Coral Reef was initiated through their non‑profit Institute for Figuring in Los Angeles to engage the public with science and mathematics. It quickly grew into a global community with over 8,000 women involved in crocheting thirty satellite reefs across the world in order to highlight environmental issues.

Western Feminism has a poor record when it comes to race relations. This disgrace is slowly being addressed through intersectional feminism and the recognition and growth of black women’s culture, scholarship and activism. Although feminism may not have translated well across cultures, especially in traditional Aboriginal culture where gender and kinship structures are different, some ways of doing things may be shared. The practice of women meeting and talking together in a personal way is part of the everyday life of many women. Women chat, gossip, and reminisce a lot with one another, across their families and generations. And this is sometimes done together with weaving, knitting, embroidering, making and decorating.

In the Western Desert across the NPY Lands women travel to facilitate family relations and meet with other women to create fibre sculptures, baskets and vessels. Jennifer Biddle argues that a significant new art form has emerged as a result and it has been successful because it accommodates the women’s way of life. She says the Tjanpi sculptures “re‑incite a certain ‘nuclear script’ of country, place and practice: a conjointly female‑specific way of being with one another, and of being in country.”[33] The Tjanpi Weavers won the prestigious National Indigenous Art Award in 2005 with a life‑size Toyota flatbed truck. The Tjanpi Grass Toyota is a witty political reminder of the colonial detritus that litters their homelands.[34] In 2016 they won a Social Enterprise Award for Women’s Impact.[35]

In this paper I have tried to map out where feminism is, at its present historical juncture, and to demonstrate the ways in which its practices, dialogues, positions and arguments are entangled over the generations. Different geographical locations have thought feminism in different ways and this is useful for establishing the depth of the field. Generationally, feminism is still young and although it has brought some pragmatic change for white, middle class and educated women, it has also opened up a huge amount of questions about gender, race, difference and equity. Hopefully in the new generation where intersectionality is motivational some of feminism’s whiteness will be addressed and gender will be accepted as a more fluid aspect of identity.

Kanytjupayi Benson, Shirley Bennet, Nuniwa Donegan, Margaret Donegan, Melissa Donegan, Janet Forbes, Ruby Forbes, Deidre Lane, Elaine Lane, Freda Lane, Janet Lane, Jean Lane, Wendy Lane, Angela Lyon, Sarkaway Lyon, Angkaliya Mitchell, Mary Smith and Gail Nelson from Papulankutja (WA). Tjanpi Grass Toyota, 2005. Photo: Thisbe Purich © Tjanpi Dessert Weavers, NPY Women’s Council © Shirley Bennet, Janet Forbes, Melissa Donegan, Elaine Lane, Freda Lane, Janet Lane, Jean Lane, Angkaliya Mitchell, Mary Smith/Licensed by Viscopy, 2017

Footnotes

- ^ Sarah Franklin et al., Global Nature, Global Culture, London: Sage, 2000, p. 6.

- ^ For a popular critique see Susan Faludi, “American Electra: Feminism’s Ritual Matricide,” Harper’s Magazine, October 2010, pp. 29-42. For scholarly appraisals, see Iris van der Tuin, “Jumping Generations: On Second- and Third-wave Feminist Epistemology,” Australian Feminist Studies, 24:59, March 2009, pp 17–31; and Clare Hemmings, “Generational Dilemmas: A response to Iris van der Tuin’s ‘Jumping Generations’,” Australian Feminist Studies, 24:59, March 2009, pp. 34-37. For an artist’s analysis of this problem see: Alex Martinis Roe and Human Poney, "“Solidarity-in-difference” and the politics of transgenerational feminism: A conversation with Alex Martinis Roe," AQNB, last modified May 8, 2017: http://www.aqnb.com/2017/05/08/solidarity-in-difference-and-the-politics-of-transgenerationalfeminism-a-conversation-with-alex-martinis-roe/.

- ^ [Ed note] For further discussion around Marina Abramović: Private Archaeology, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, 13 June – 5 October 2015; and the 30th Kaldor Public Art Project, Marina Abramović: In Residence, Pier 2/3, The Rocks, 24 June – 5 July 2015, see Anne Marsh, ‘Marina Abramović: Mindful immateriality’, Artlink 35:3, September 2015, pp. 18–23: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4363/marina-abramoviC487-mindful-immateriality/.

- ^ Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Australian Feminist Studies, 2:4, 1987, pp. 1–42.

- ^ See for example, Ray Kurzweil, The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, New York: Viking Books, 2005.

- ^ Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007, p. 132.

- ^ For the criticisms, see Richard Haese, Permanent Revolution: Mike Brown and the Australian Avant-garde 1953–1997, Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Deborah Clark, “The Painting of Vivienne Binns,” Vivienne Binns, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart: TMAG, 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” in Lenin and Philosophy, trans. Ben Brewster, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971, pp. 127–86.

- ^ See Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, Autumn 1975, pp. 6–18; and Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”, New York: Routledge, 1993.

- ^ Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter, p. 29; as quoted in Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, p. 150.

- ^ I have covered these arguments in detail in my book Look: Contemporary Australian Photography since 1980, South Yarra: Macmillan, 2010. See especially “The Body and Performative Photography,” pp. 355–65.

- ^ 13 For a lucid analysis see Robyn Wiegman, Object Lessons, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012, esp. chapters 1–2.

- ^ See Anne Enke, “Introduction: Transfeminist Perspectives” in Enke (ed.), Transfeminist Perspectives In and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies, Temple University Press, 2012, pp. 1–8.

- ^ For a critical discussion of The Dinner Party, including participants in the project, see Isabel Davies (ed.) “The Coming Out Show” discusses “The Dinner Party” in LIP, 1980, pp. 48–50. For an assessment of the Australian showing see Kate MacNeill, “When Historic Time Meets Julia Kristeva’s Women’s Time: The Reception of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party in Australia,” Outskirts, 18, May 2008: www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au/volumes/volume-18/macneill.

- ^ See Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Margaret Waller, New York: Columbia University Press, 1984 and Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. For a critique of Kristeva see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “French Feminism in an International Frame”, Yale French Studies, no. 62 1981, pp. 154–84.

- ^ Luce Irigaray, Divine Women, Local Consumption, Occasional Papers, no. 8, Sydney: Local Consumption Publications, April 1986, pp. 1–14. First published in French in Critique, 454, Mars, 1985.

- ^ Luce Irigaray, “Equal to Whom?”, in Naomi Schor and Elizabeth Weed (eds.), The Essential Difference, Bloomington and Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1994, pp. 63–81

- ^ See especially: Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories, London and New York: Routledge, 1999; and with Fred Orton, Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1996

- ^ See Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, “Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed” in Pollock and Orton, Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed, pp. 141–64 and Francis Frascina (ed.), Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, London and New York: Routledge,1985

- ^ Rosalind Krauss, “. . . And Then Turn Away? An Essay on James Coleman’, October, no. 81, 1997, p. 5. Also Rosalind Krauss, “Reinventing the Medium”, Critical Inquiry, winter 1999, pp. 289–305. For the debates on the post-medium and its ramifications see George Baker, “Photography’s Expanded Field”, October, no. 114, Fall 2005, pp. 120–140. An example of a return to traditional aesthetic values is found in Michael Fried, “Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein, and the Everyday”, Critical Inquiry, no. 33, Spring 2007, pp. 495–526 and his monumental text Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008

- ^ Two recent exhibitions showcase this work. The modest touring exhibition Abstraction: Celebrating Australian Women Abstract Artists, exh. cat. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2017; and the National Gallery of Victoria’s Who’s Afraid of Colour, 16 December 2016 – 16 July 2007, that highlighted the enormous contribution of Aboriginal women artists to the field.

- ^ Vivienne Binns, ‘Mothers’ Memories, Others’ Memories’, LIP, 1980, pp. 38-45 .

- ^ Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance, Fronza Woods and Mathieu Copeland, Paris: Les Presses de Réel, 2002, pp. 25–40. First published in French 1997.

- ^ See Kathie Muir, “Art and Working Life Revisited: Where to from Here”, Art Monthly, no. 64, October 1993, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’”, October 110, Fall 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Claire Bishop, Ibid. p. 54.

- ^ Controversially, The Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective argued against emancipation for women saying it assimilated women into the male model and made her contemptuous of her own sex. They argued instead that women should engage in the “struggle for a sense of ease” that prioritised “the articulation of emotions” and led to “the diminution of anxiety”. See Libreria delle Donne di Milano, “More Women than Men” (1983), in Paola Bono and Sandra Kemp (eds.), Italian Feminist Thought: A Reader, Oxford UK and Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basil Blackwell, 1991, pp. 114 and 122.

- ^ Alex Martinis Roe in correspondence with Anne Marsh, 8 August 2017 .

- ^ Among other things, the film documents the Philosophy strike of 1973 at Sydney University which was precipitated by the cancellation of a women’s studies course.

- ^ See Kirsty Robertson, “Rebellious Doilies and Subversive Stitches: Writing a Craftivist History” in Maria Elena Buszek (ed.), Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011, pp. 184–203.

- ^ See Kyra Clarke, “Willful Knitting? Contemporary Australian Craftivism and Feminist Histories”, Continuum Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 30:3, 2016, pp. 298–306.

- ^ Jennifer Biddle, “A Politics of Proximity: Tjanpi and Other Experimental Western Desert Art”, Studies in Material Thinking, vol. 8, May 2012, p. 9: http://www.materialthinking.org.

- ^ “Tjanpi Desert Weavers: A New Spin on Indigenous Art: http://www.artcollector.net.au/TjanpiDesertWeaversAnew SpinonIndigenousArt; and Lindsay Murdoch, “Oh what a weaving: Grass Toyota wows judges”, 13 August 2005:http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/oh-what-a-weaving-grass-toyota-wows-judges/2005/08/12/1123353507268.html

- ^ Tjanpi Weavers describe themselves as an enterprise for women on their web site. They have won numerous awards including: A Social Enterprise Award for Women’s Impact, an Ethical Enterprise Award in 2016 and a Deadly in 2012. The group represents over 400 Aboriginal women from 26 remote communities on the NPY lands. See