© 2025 professor ANNE MARSH | SITE BY jamie charles schulz

PUBLISHED IN

This article first appeared in the AHRB Research Centre for Studies in Surrealism and its Legacies, no. 6, 2007, University of Essex and University of Manchester, on-line journal.

CATEGORY

Photography, Surrealism

YEAR

2007

A Surrealist

Impulse

Pat Brassington's photographs began to receive critical attention in the 1980s when photographic theory and criticism was experiencing a renaissance.

Her work spoke loudly in a postmodern culture that deconstructed notions of the original and authenticity, interrogated the epistemology of the gaze and the stereotypes of feminine sexuality. Her use of found photographs, collage and digital manipulation marked her clearly as an artist who engaged with the reproducibility and performativity of the medium. Brassington is part of a generation of post-feminist artists who followed on from the breakthroughs made by Cindy Sherman in the US and Mary Kelly in the UK. Although Brassington does not photograph herself exclusively, she does embrace a performative approach to photography, which is used to situate an uncanny female presence. Like Mary Kelly, she is interested in psychoanalysis and how the subject is inscribed in language, although Brassington's work does not have the same political compulsion.

Performative approaches to photography are ubiquitous in contemporary work, much of which has a surreal impulse as well as drawing on performance art actions. Rebecca Horn's Arm Extensions (1970) and Louise Bourgeois's Costume for A Banquet (1978) are early examples. This practice continues with artists such as Yasumasa Morimura who, like Cindy Sherman, uses his own body to act out multiple personae. Anna Gaskell's series By Proxy (1999) explores fantasy and real-life stories to present a sinister and seductive picture of a nurse who murdered her young patients. There is a surreal edge to this narrative in Gaskell's series, which has something in common with Pat Brassington's exploration of the dark underside of lived experience. But Brassington's work is more abstract and difficult to pin down since the narrative is always confounded for the viewer. Writing about her work in 2004, she said:

I have long been interested in psychoanalysis and have been intrigued also by strategies used by some Surrealists. If I add these influences to my own life experience I come as close as I can to providing a rationale for my images of fantasy."1

Fig. 1: Pat Brassington, Lisp, 1997, pigment print, 110 x 80cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 1: Pat Brassington, Lisp, 1997, pigment print, 110 x 80cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

In most of her 'artist's statements' and the rare interviews in press, Brassington mentions her engagement with both surrealism and psychoanalysis.2 But there is no allegiance, no endorsement, no salute to the father. Everything is troubled in one way or another: from horror imagery that is violent and abject, through the hauntingly strange and uncanny, to the hideous, the hilarious and the banal. Brassington interrogates and extrapolates on the psychoanalytic in extreme ways: orifices exhale, threaten and protrude; the feminine is hysteric, phallic, powerful; the father is demented, perverted (the pre-version of the father) and menacingly psychotic.3

If Brassington is informed by psychoanalysis it is more likely through the veil of Georges Bataille and Andr Breton rather than the canon of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. All the surrealists were concerned with the dream and the real and convergences that would propel a 'sur-real' result but they emphasised different processes. For Breton, automatism and automatic writing or drawing were fundamental to surrealism and provided a way to tap the unconscious. He argued that: 'any form of expression in which automatism does not at least advance undercover runs the grave risk of moving out of the surrealist orbit.'4 Breton was enthralled by the kinds of associations that arose through automatism and believed that this gave rise to what Rosalind Krauss has called a 'rhythmic unity.'5 Krauss argues that this is 'akin to what Freud called the oceanic feeling - the infantile, libidinal domain of pleasure not yet constrained by civilisation and its discontents.'6 In contrast, Bataille prioritised the nightmare rather than the dream: what was excluded, devalued, ugly, bestial and excessive was used to investigate subjectivity and desire and to critique European society after the First World War. The hindsight of history allows Pat Brassington to plunder the surrealist archive so that in her work we see the influence of both Breton and the more renegade approach of Bataille. In Lisp, for example, a child's face emerges from a watery or uterine space as if caught in a dream [fig. 1.]. A pink flower lies on her lips creating a delicate silence. In The Gift and In my Father's House, discussed below, the dark side of the unconscious is foregrounded and the viewer enters into nightmarish territory [figs. 2 and 3].

Feminists have often critiqued Brassington's work with reference to Julia Kristeva's thesis about the subversive potential of the pre-Oedipal space and experience where the abject is a threat to the social order.7 The abject is what spills out from the body and cannot be contained: tears, vomit, sexual excretions, blood. It is characterised by the body seeping from its own containment (the skin), and tumbling into the social world unannounced. The abject body creates a kind of awe and fear in the viewer and as such has a radical edge in representation. Like the pre-Oedipal space before language, the abject threatens to topple polite social conventions.8 But, like the surrealists, Brassington interacts with psychoanalytic experience rather than adhering to any particular school of thought. As an artist aware of feminist art criticism, she undercuts the misogyny sometimes associated with the surrealists' representations of feminine sexuality and their romantic notion of the female muse who was invariably fetishised through male desire. In her work sex, sexuality, desire and the sensual are evoked in a series of bizarre mise-en-scnes that present flashes and glimpses of dreamlike states. These invoke hysteria and psychosis but do so by looking at fears, fantasies and traumas with a gaze that is importantly awry. This skewed perspective on the psychosexual landscape allows the artist to become a kind of conjurer. In an exhibition catalogue of 1989, the artist quoted Bataille:

Now the average man knows that he must become aware of the things which repel him most violently. . . Those things which repel man most violently are part of his own nature.”9

The troubled psyches of men and women recur in Brassington's work, and sometimes this encounter is filtered through images circulating in the public domain, such as film stills, while at other times the artist uses found images from amateur family albums, sometimes her own. This scavenging of images then undergoes a surrealist treatment as they are cut, sliced, doubled, damaged and re-contextualised. Like Breton and Bataille, Brassington is concerned to create juxtapositions and uncertainties between images that will open a space for the troubled unconscious to be represented. Her early work (c.1986-94) takes cinema, especially the horror and science fiction genres, as an archive of images that can be mined. These are then arranged alongside a host of other images which may be taken from high art, the nineteenth-century medical archive, the natural history museum, and the family album. Brassington acts as a kind of miner bird, an eclectic thief who traverses borders and takes what she fancies. She is also a postmodern scavenger of found images, an appropriationist, and a teaser who constructs visual puzzles to which there are no correct answers.

The solo exhibition titled Eight Easy Pieces (1986) is an example of Brassington using the archives of cinema and high art to create ensembles of images that appear as if moments of terror, ecstasy and pain have been sliced out of context. Most writers who have written about this work have interpreted it through the screen of psychoanalysis.10 But Brassington's work slides around theoretical positions and is always difficult to pin down. There is no doubt that the artist has a thorough knowledge of psychoanalysis, but her work questions the theoretical canon, both from the position of woman (the one who in Lacanian theory does not exist) and from the position of the artist who is also free to play the maverick and make trouble through imagery.

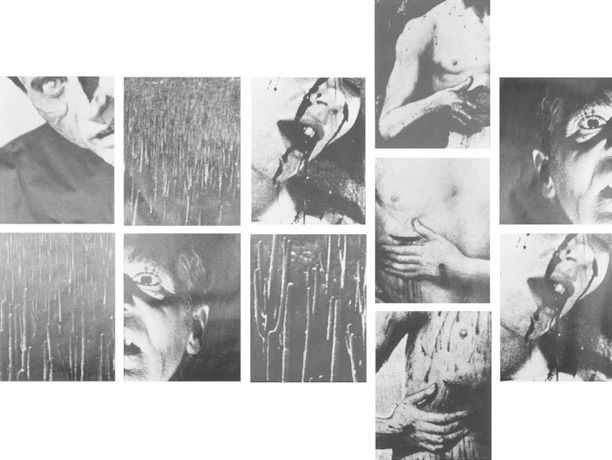

Fig. 2: Pat Brassington, The Gift, 1986, eleven silver gelatin prints, 140 x 220cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 2: Pat Brassington, The Gift, 1986, eleven silver gelatin prints, 140 x 220cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Images from Eight Easy Pieces, like many of Brassington's works, can be read awry, and it is this aspect of her work that makes it both compelling and timeless. In The Gift, for example, black and white reproductions of late Renaissance paintings showing 'The Man of Sorrows' are appropriated into the set of a modern horror movie where Christ displays his open wounds after his resurrection, with one image showing Christ's finger probing the wound, perhaps to appease doubting Thomas [fig. 2]. The three images of Christ make up the vertical fulcrum of the display cutting the eight other (easy) pieces to form a horizontal cross, fallen on its side. Christ's cropped torso is flanked by a three-quarter view of a woman s face sliced off at the left eye with blood pouring from a wound off screen.11 The woman has her other eye closed, and her mouth is open, but she doesn't appear to be screaming. She could be already dead and lying on the ground. However, seen vertically in Brassington's grid, the woman could also be in a state of ecstasy. Her face is repeated twice, as is the adjacent image of half of a man's face, one a mirror flip. He looks up in awe, but is he actually frightened? A bright light shines from above him as he stares upon the unknown, suggesting the presence of an unseen UFO. Four other images make up the fallen cross. Three dark - almost black - pictures of fields of cacti at night appear at first glance to be either lines, rivulets of water or light, or prickly tears for the man of sorrows. But before we get too complacent about the ecstasy of religious sorrow, the final image, completing the sliced eight, is the quarter face of a ghoul who looks into the deathly constellation. Looking quizzically through one bulging eye he unveils the fantasy; acting as the maverick onlooker he presents an irreverent humour. Talking about these works in 1986, Brassington said that they 'are pitched just off the verge of normality into those dense patches where, mediated by our phantasms, our fears peer back at us.'12

Looking closely at The Gift, we can see how Brassington uses the tools of the film director with a keen eye on an experimental, avant-garde method, which slices and cuts up narrative sequences to make montages which operate, at their best, as a mark of resistance to conventional language. Every viewer will put the images together in different ways, and in the end the experience may be exhausting and frustrating since the images resist our desire for closure. These collated images are like triggers that tempt our fears. If they represent anything specific it is the movement of desire captured by the glance, a desire that is forever circular and certain never to be satisfied. This is what draws us in: the postponement of satisfaction, which is the mechanism of desire's becoming.13 The example of The Gift and my interpretation of it show how Brassington traps the gaze (and the desire) of the viewer. Just when we have developed a story, it collapses upon itself, in this case through the eye of a ghoul who lusts after the dead to feed upon them.

Social taboo, and the uncanny, fantasy, voyeurism and desire are all conceptual fissures that run through Brassington's work. But, being an artist, she is able to use these ideas wilfully and irreverently. She is quick to embrace Freud's idea that the unconscious can never be represented, something that intrigued the surrealists. However, Freud argued, it can be glimpsed momentarily in jokes, dreams and slips of the tongue.14 Brassington mines this idea in an attempt to show us what is usually unseen in our daily lives. After the mid-1990s she concentrated almost exclusively on this aspect of lived experience, trying to give us a glimpse of what is unsaid and unseen. These included moments in dreams, the punch line of a joke that may miss its mark, and images that push the boundaries of the normal, bordering on the phantasmagorical.

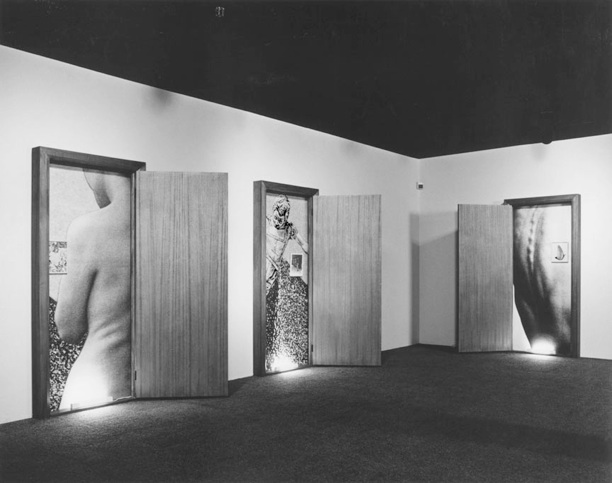

Fig. 3: Pat Brassington, In my Father's House, 1992, three silver gelatin prints, three photocopies, three wooden doors, fluorescent light fittings, 230 x 800cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 3: Pat Brassington, In my Father's House, 1992, three silver gelatin prints, three photocopies, three wooden doors, fluorescent light fittings, 230 x 800cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Brassington's work often draws on images from her own family album but it is rarely autobiographical and never self-expressive. However, some of the works appear to deal more explicitly with the artist's own psychosocial construction and personal experience than others. In my Father's House (1992 version) is a mixed media work consisting of three doors hung on frames that open onto large digitally manipulated photographs [fig. 3]. Two of the images show a monumental close up of the back of a naked body and they stand on either side of an image of a child, appropriated from an 1881 issue of the London-based Art Journal, according to the artist's recollection. This figure seems to be airborne and flies through a domestic interior, while Brassington has added a small inset black and white image of another child on a walk through a suburban laneway. The female figure to the left looks away from the viewer: she is cropped below her ears and at her buttocks, her left arm folded over her stomach, and she looks into the same domestic space, like a witness. Another small inset image sits to her left, showing a colourful spray of roses. The final image shows the arched back of a male figure with the skeletal structure of the spine clearly visible. This back takes up almost all of the frame. Inset on the right hand side is an image cropped from a nineteenth-century medical book showing an erect pink tongue emerging from a mouth with the figure number from the original source still visible. The tongue is swollen or injured, and it may have been surgically stitched. As it stands erect on the male figure's back the reference to the phallus is prominent.

Fig. 4: Pat Brassington, In my Father's House, 2004, detail, door measurement 200 x 100cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 4: Pat Brassington, In my Father's House, 2004, detail, door measurement 200 x 100cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

In the second version of In my Father's House (2004) the figures are the same but the viewer encounters the doors ajar rather than wide open and must open the doors to see the photographs. The inset image of the tongue recurs on the back of the male but the female figure now has a pink seashell covering her left shoulder. The child has a pink teddy bear (or gingerbread man) over her heart. The bear is propped in the corner of a room and seems to have been made out of minced meat. I can see an eyeball and a pair of snarling teeth in the head and neck region. The digital rendering has created scarring which seems to pierce the flesh, as if this is a kind of voodoo doll [fig. 4].

The sequence of images in both versions is fanciful, with a strong undercurrent of menace made more obvious in the second. The teddy bear figure is grotesque and points to some horrible violence lurking in the fairytale image of the illustrated child. Barbara Creed has suggested that the installation points to the violation of the female.15 To me the images are also about repression; what is left unsaid but runs throughout the family structure. This is certainly a theme that recurs throughout Brassington's work and is a dominant subject in In my Mother's House, where the female figure appears as if she were an hysteric from one of Jean-Martin Charcot's late nineteenth-century seminars at the Salptrire clinic [fig. 5]. There are two figures in the mother's house: one a young female figure who stares out of the picture but beyond the viewer clearly in another state of mind. The other is a phallicised depiction of a young boy's neck that references Man Ray's famous Anatomies of c.1930. Between the girl and the boy is a pillow which belonged to Brassington's mother and recurs in other sequences. To the left of the hysteric girl is a reproduction landscape scene hanging on a wallpapered wall.

Fig. 5: Pat Brassington, In my Mother's House, 1994, four silver gelatin prints 52 x 142cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 5: Pat Brassington, In my Mother's House, 1994, four silver gelatin prints 52 x 142cm (overall dimensions). Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Kyla McFarlane has argued lucidly that much of Brassington's work is a 'feminine diagnosis of discontent, often directed at the father.'16 However there is also discontent directed at the mother, the feminine construct itself and the structure of the Oedipal, patriarchal family. McFarlane is careful to use the term 'the father' to indicate the language of psychoanalysis where the term is used to designate the symbolic order, language and social law. Women also speak in the name of the father; in fact everyone who avoids psychosis enters into the prison house of language where that which cannot be spoken - the pre- Oedipal, the Real, the unconscious - is repressed. Although the installations that refer to Brassington's own family are drawn from her own experience they speak loudly to a wider agenda, specifically sexuality in the family structure. In my Mother's House is a signature work in many respects as it predicts what will follow. Here the hysteric girl child is alienated from the powerful yet deformed phallic mother by a pillow that could be used to smother the child. But the symptom, the hysteria, is everywhere, even in the wallpaper which frames the 'natural' landscape. There is a sense of airlessness and an intensity between the two female figures which suggests that all is not well in the house of the mother.

At the heart of these installations is a desire to unveil the Real, to get to the bottom of things. This is what makes Brassington's works tremble with a kind of unspoken violence. The could-be smothering mother, the perhaps tyrannical father and the hysteric child inhabit these pictures. But none of these things can be represented, and if they were it would be via a conventional narrative, a Hollywood storyboard. This is not what Brassington wants to convey. Her methodology is more radical than that. She wants to hint at the unrepresentable, hoping that it will come forward in the imagination of the viewer. For the most part she is successful, but it is only in her nurturing of doubt that she is able to get us, the viewer, to imagine what is not said. Like Slavoj Zizek she probably agrees that: in our unconscious, in the real of our desires, we are all murderers.17 Writing about the uncanny in Hollywood films, Zizek says:

& the uncanny gaze . . . subverts the border between life and death, since it belongs to a dead object (corpse, doll), which nonetheless possesses a gaze of melancholic expressiveness.”18

Freud's notion of the uncanny is exploited in much of Brassington's imagery, as here what is homely and familiar becomes unhomely, unfamiliar, strange. The uncanny haunts the everyday and is sometimes experienced as a sense of unease, a kind of deja-vu when we sense that we have seen this or been here before. This feeling of history repeating itself is intimately tied up with imaginary/psychic memory which is incomplete and fragmented, full of lost images and repressed fears. This kind of imagery circulates in the cultural imaginary and comes alive in art, literature and film. Brassington operates as a kind of archaeologist of the uncanny, picking over the ruins of conscious life and lived experience to find something beneath the surface which excites fear.19

An uncanny aspect runs through much of Brassington's work. In Pond, the images are presented as evidence, as if they belonged to a police investigation of a crime that is difficult to establish. The twelve images that make up the series are close-ups of objects that have been submerged in water, ordinary things that in a sodden and drowned state take on an extraordinary sexual effect. However, Pond is also playful and clearly references the Surrealist photographer Man Ray who pictured a man's hat from above, shot to resemble a woman's vulva (Untitled, 1933). The uncanny is often associated with things that are dead that appear to be alive. Freud gives the example of dolls and ghosts, and we could easily add the dummy and the mannequin. These are inanimate things which act as doubles and stand-ins for the body or psyche. Our fear is that these things will become animate and take on a life of their own. These sorts of 'things' recur throughout Brassington's work. In fact her method of producing imagery is often repetitious and the return of the repressed image or scene haunts the work.

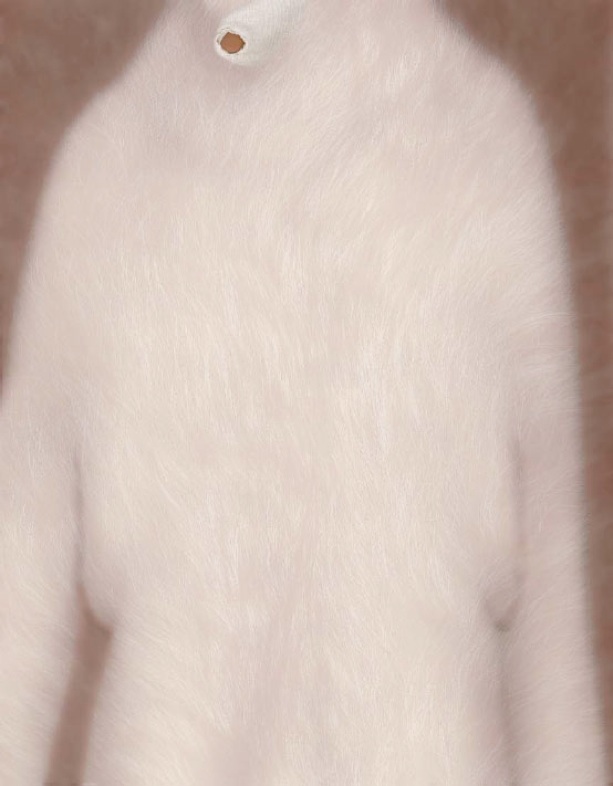

Fig. 6: Pat Brassington, This is not the right way home, 2003, pigment print, 75 x 58cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Fig. 6: Pat Brassington, This is not the right way home, 2003, pigment print, 75 x 58cm. Courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney, Arc One Gallery, Melbourne and Criterion Gallery Hobart.

Many writers have emphasised Brassington's focus on the feminine and the female body.20 It is certainly the case that there is a thorough exploration of sexuality, but the gender positions are often blurred. Brassington is also engaged with repetition as a psychoanalytic device and prefers the ambiguity of sexual positions and identities. The boundaries of the body are often made fluid in her images: things appear where they shouldn't, bits penetrate each other in strange ways and fluids are interchangeable. Boucher (2001), for instance, is a disturbing image of body parts. In the upper left a fragment of the pubis (or is it underarm hair?), peeks into the picture. Two legs squeeze together, or an arm squeezes against the chest to create a channel between them. A phallic object, probably a finger, penetrates the flesh in an unsuspected place. It is this probe that pierces into the body that is abject and uncanny. The body is pink and soft but the fleshy probe is an alien object, a cancerous growth made pretty. Boucher is a horrible image but it also resonates with a dark humour. The viewer knows that it is constructed but this knowledge is not settling. This is not the right way home is even more unsettling [fig. 6]. Here the body is pink and flabby and bathed in a painterly shimmer, while the torso has a growth protruding from the neck area, like an enlarged post-operative hole for breathing directly into the larynx. The figure is ghostly and otherworldly, deformed in the flatness of its torso and by its decapitated head. It could easily be a ghost.

Brassington plays with horror; she delights in finding images and cutting them up, then putting them together in ways that create a kind of psychological puzzle for the viewer. Everything is unnatural, and a madness runs wild throughout the work. Here the artist tempts the unconscious and sets traps for the gaze. She says that in the process of selecting and remaking images she tries to stop short of any resolution, remaining decisively indecisive, saying again and again what they are not. In relation to this, several writers have warned against any type of psychoanalytic interpretation of Brassington's work.21 Edward Colless says it best when he argues that: 'To decode the patterns of the correspondences as if they were symbolic would [be] like trying to psychoanalyse the window of a tumble dryer.'22 Venturing into the visual world of the abject, the opened body, the oozing wound, is dangerous. However, the territory has been mined by many artists, most notably the surrealists, and more recently the directors of horror movies. Brassington knows this territory well and she works to distort the borders of the abject and the unknown by enticing the medium to act up. In her own words, she says:

“Too much digging into one's motivation runs counter to free flowing spontaneity, but I do seem to be attracted to the enigmatic. When morphing an image I baulk prior to resolution and prefer to leave it hovering in uncertainty. Our visual brain endlessly seeks resolution and hence the real exerts a magnetic attraction. My aim is to use this gravitas to spin off towards other possibilities.”23

Notes

1. Pat Brassington, artist's statement, published in Supernatural Artificial: Contemporary photobased art from Australia, curated by Natalie King, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2004, 12

2. Diana Klaosen, 'An Interview with Pat Brassington,' Imprint, vol. 33, no. 2, 1998, 9.

3. }i~ek notes that Lacan prefers to write perversion as pre-version, i.e. the version of the father.' Slavoj }i~ek, Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1991, 25.

4. Andr Breton, Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor, Harper and Row, New York, 1972, 68. Philippe Soupault says that he and Breton adopted the practice of automatic writing from the French psychiatrist Pierre Janet for their book Les Champs Magnetiques, see Elizabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan and Co.: A History of Psychoanalysis in France, trans. Jeffrey Mehlman, University of Chigaco Press, Chicago, 1990, 12.

5. Rosalind E. Krauss, 'The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism,' in The Originality of The Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1986, 95.

6. Krauss, 'The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism,' 95.

7. Brassington's imagery is steeped in a type of feminist psychoanalysis which was made popular by Julia Kristeva and absorbed into cinema studies in Australia, initially through the works of Barbara Creed. See Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Columbia University Press, New York, 1992; Helen McDonald, Erotic Ambiguities: The Female Nude in Art, Routledge, London and New York, 2001, 180-185; Catriona Moore, Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1991, 141-143, and Barbara Creed, 'Horror and the Monstrous Feminine - An Imaginary Abjection,' Screen, Jan-Feb, 1996, 44-70. See also my 'Pat Brassington: Uncanny Witness,' Art and Australia, vol. 41, no. 4, Winter 2004, 586-592.

8. In the conventions of psychoanalysis, the child travels from a pre-Oedipal state (before language) into an ego identity which is contained and made possible by language. As the two year old experiences a tantrum, screaming incomprehensibly about what she wants, the adult says speak to me: say what you want. This is the socialising mechanism of all societies and what allows us to communicate. In so doing we leave the pre-Oedipal state behind and repress the fears of the imaginary realm albeit unsuccessfully. These fears return in dreams.

9. Georges Bataille, as quoted by Pat Brassington, in an artist's statement for a solo exhibition at Chameleon Contemporary Art Space, Hobart, in 1989. The statement consisted primarily of a collage of quotations from Bataille and Lewis Carroll.

10. See for example Moore, Indecent Exposures, 141-144, and McDonald, Erotic Ambiguities, 180-186.

11. When I was corresponding with Pat Brassington about this project she told me that when she produced Eight Easy Pieces she had her brother's death in mind. This puts a particularly poignant and personal emphasis on the 'man of sorrows.'

12. As quoted in Jonathan Holmes, 'Pieces of Eight,' Photofile, Spring 1986, 15.

13. }i~ek says desire is circular; it is the postponement of satisfaction, Looking Awry, 11.

14. Sigmund Freud, Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 8, trans. James Strachey, Hogarth Press, London, 1930, and Norton and Company, New York, 1962.

15. Barbara Creed, 'The Aberrant Object: Women, Dada and Surrealism,' Art Monthly, no. 69, May 1994, 12.

16. Kyla McFarlane, 'Pat Brassington: Work in Progress,' Eyeline Contemporary Visual Arts, no. 50, Summer 2002-2003, 18.

17. }i~ek, Looking Awry, 16.

18. }i~ek, Enjoy Your Symptom! Jacques Lacan in Hollywood and Out, Routledge, London, 2001, 121. The author is writing about an early Blake Edwards thriller Experiment in Terror.

19. Freud, 'The Uncanny' (1917-1919), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psycho-analytic Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. J. Strachey, Hogarth Press, London, 1950, vol. 17, 219.

20. See Jennifer Soinks, 'Bad Light,' Art and Australia, vol. 32, no. 4, Winter 1995, 586, and Jane Deeth, 'When You Get Behind Closed Doors,' Artlink, vol. 16, no. 1, Autumn 1996, 80- 81.

21. See Marsh, 'Pat Brassington: Uncanny Witness.'

22. Edward Colless, 'Ghost,' exhibition catalogue essay in This is Not a Love Song: Project Room: Pat Brassington, Monash University Gallery, Clayton Victoria, 1996, 12.

23. Pat Brassington, artist's statement published in Supernatural Artificial, 12.