Politics

& Poetics

The Medium as a Ghost - Works by Peter Kennedy

PUBLISHED IN

Originally published in Hilde Van Gelder and Helen Westgeest (eds.), Photography between Poetry and Politics: The Critical Position of the Photographic Medium in Contemporary Art, Leuven UP, 2008, 99. 19-34.

CATEGORY

Political Art, Postmodernism

YEAR

2008

Politics

& Poetics

In the late 1990s scholars in the USA warned against the convergence of art and theory where practice appears to pitch itself to critical discourse or seeks to engage in that discourse.1

Rosalind Krauss has termed the current era the “the post-medium age in which the aesthetic option of the medium has been declared outmoded, cashiered, washed-up, finished”.2 For Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster much of postmodern art was either a continuation of critical modernism and/or the critical edge of postmodern practice (pastiche, irony, appropriation) was quickly absorbed by the capitalist market which acclaimed the plurality of postmodernism as part of a liberal platform.3

Krauss is concerned that post-medium art is blurring the boundaries between disciplines too much. She argues that photography plays a major role in postmodernism because it “restructures the conditions of the other arts”,4 however she laments the loss of the aesthetic medium.5 For Krauss and Foster the critical, deconstructive edge of what Foster once called a postmodernism of resistance has lost its critical clout and is now used in the service of global capital.6 For Krauss the artist is now compelled to revisit the medium, to analyse the aesthetic conditions of the medium from within. For Foster the artist and the critic need to re-visit history to understand how it is being repeated in the present.

Rosalind Krauss wants to return to the idea of the medium as a physical support or recursive structure in order to curb the international phenomenon of installation art and the problematics of the post-medium age.7 However, the residual essentialism of this idea, which was exploited by Clement Greenberg and critiqued thoroughly by postmodern critics from the 1960s onwards, cannot be evaded. It seems counter productive to insist on such a return to essentials when so much of contemporary art practice is either interdisciplinary or engages with the formal dialogues of several mediums at the same time. Krauss recent condemnation of post-medium art seems somewhat contradictory since her essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field was one of the most important essays of the 1980s to explore the cross-disciplinary nature of the visual arts.8

It is interesting to note Krauss agreeing with Clement Greenberg's formulation of the autonomy of the arts. Greenberg's argument was also a kind of defence; a defence of the avant-garde predicated on the essential qualities of high art painting and sculpture. The essentialism of the disciplines would protect the autonomy of the disciplines. Greenberg's other agenda, one which has generated considerable criticism, was to argue that the avant-garde should be separate from society, not engaged with social issues but only with the essential wetness of the paint and the flatness of the colour field. If artists did this they would avoid the horrors of popular/mass culture: kitsch.

Peter Kennedy has always been a political artist. He identified with the neo avant-garde of the late 1960s and 1970s and sought to position Australian artists like himself on the international stage. He was one of only three Australians to have an entry in Lucy Lippard's book Six Years: the de-materialisation of the art object and he championed the idea of mail art and instruction works that could be easily shipped across hemispheres.

Receptacle for Dreams

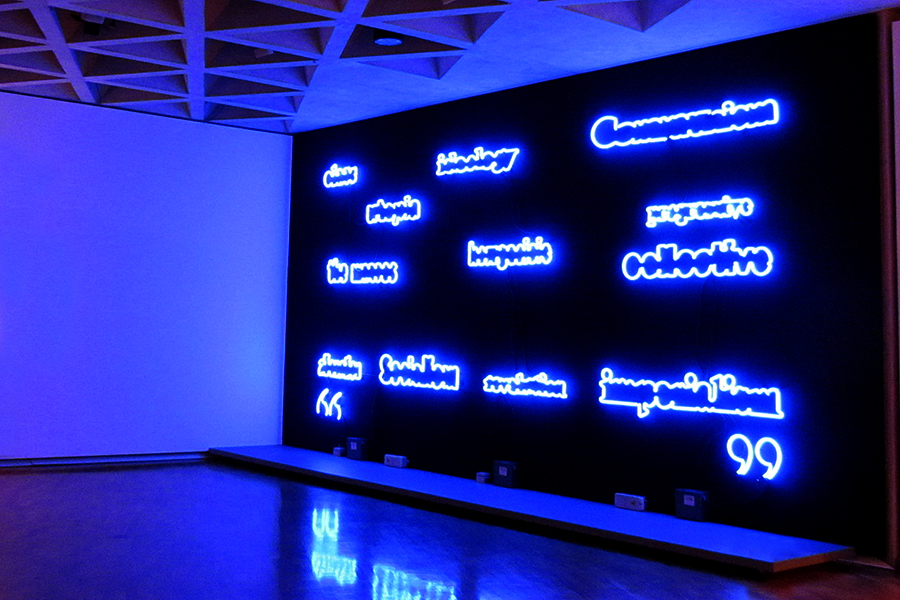

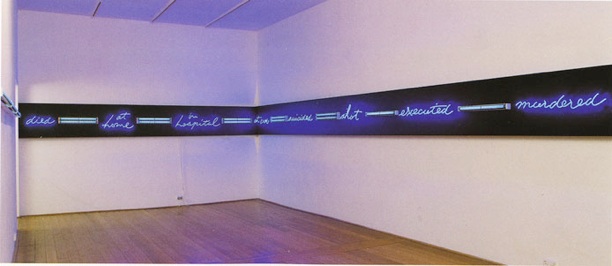

Peter Kennedy, installation view of A Language of the Dead, 1997-1998, from Requiem for Ghosts, Blue neon light mounted on freestanding timber panel. 3120 x 6460 x 300 mm. Photo: K. Pleban.

Peter Kennedy, installation view of A Language of the Dead, 1997-1998, from Requiem for Ghosts, Blue neon light mounted on freestanding timber panel. 3120 x 6460 x 300 mm. Photo: K. Pleban.

Peter Kennedy has been committed to the making political art throughout his life. He is not a medium specific artist: he makes films, videos, photographs; he assembles sculptures, works with neon light and paints; he also writes stories. Kennedy may be typical of the kind of artist that Rosalind Krauss wants to dismiss because his best and most mature work is primarily exhibited as installation. Although we can look at individual works from particular series in isolation, to do so is to shut down the noise that is Kennedy’s message to the world.

Peter Kennedy has consistently worked across visual media and incorporated old and new technologies and techniques. It is not coincidental that he is drawn to the writings of Walter Benjamin who is famous for his essay 'Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction'. This essay fleshed out the conundrum of aesthetics and politics endemic within photo-based media and film.

In the most quoted passage from the Artwork essay Benjamin says: "for the first time in world history, mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual . . . Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice politics".9 But this cuts both ways the aestheticisation of politics (Fascism) and the politicisation of aesthetics which is, according to Benjamin, the task of Communism.10 There are also celebratory moments in Benjamin's discussion where he considers mass culture to be linked to mimetic modes of perception in childhood. Indeed, harnessing the childhood dream to a revolutionary praxis was part of his understanding of the corporeality of the optical unconscious.11 According to Benjamin photography and film opened-up new sensory experiences and different modes of perception for the viewer, neither of which could be judged in terms of past art forms.

Modern Quartet: Marx, Lenin, Mao etc

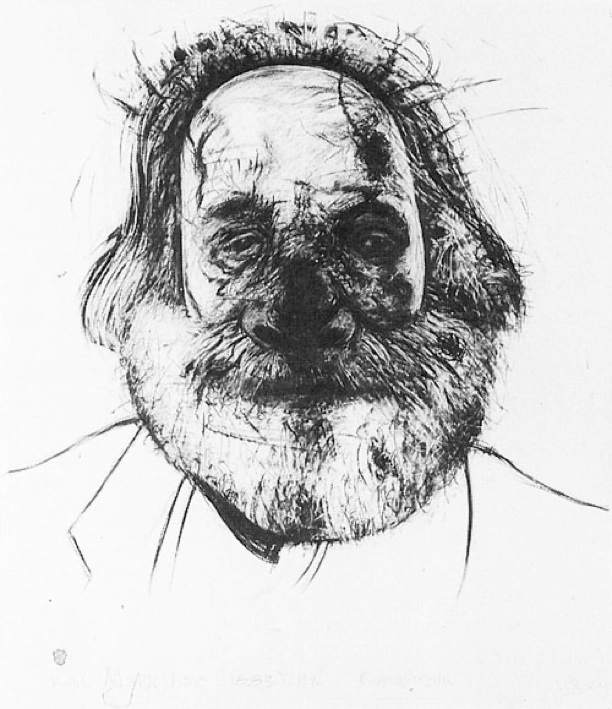

Peter Kennedy, Modern quartet, 1992. Karl Marx (1818-83) Charcoal on paper, 176 x 151 cm

Monash University Museum of Art Collection, Melbourne.

Peter Kennedy, Modern quartet, 1992. Karl Marx (1818-83) Charcoal on paper, 176 x 151 cm

Monash University Museum of Art Collection, Melbourne.

However, these utopian statements were tempered by warnings about the aestheticisation of politics. This is particularly evident towards the end of the Artwork essay where Benjamin describes the effects of a Fascist and totalitarian aesthetic that was to sweep through Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union as the Nazis, Mussolini and Stalin rose to power. The anaesthetisation of the mass audience was thus framed within its historical context.

Back to Receptacle

Like many Left wing thinkers and artists, the relationship between aesthetics and politics has concerned Peter Kennedy. Throughout his opus, from the early, minimal, neon installations, through performance, participatory art, art/film collaborations, drawing and photographic installations, to the large scale sculpture and mixed-media works of the late 1990s and 2000s, Kennedy has developed a political poetics that has challenged the concept of what art is.

Peter Kennedy is an artist who developed against the grain of postmodernism. When other artists were revelling in their status as 'already written' and celebrating the deferral of meaning associated with various post structuralist theories, Kennedy was still interrogating the analysis of culture developed by the Frankfurt School. The artist remained committed to the idea of praxis which for him meant a meeting of experimental modes of art and radical political critiques of culture.

Kennedy's art practice represents a politically engaged strategy which reflects some of the initial concerns of an earlier modernist avant-garde; concerns that were subsequently revisited by some of the neo avant-garde artists of the 1960s and 1970s, issues which recurred throughout the postmodern era. Bridging the gap between art and life, and making art more relevant to society would occupy the artist for decades.

Today I want to concentrate on Kennedy’s late works and to start with the 1990s. In Requiem for Ghosts (1998) Kennedy concentrates on the theme of mourning, creating a meditation which includes his own private experiences of near death. This work also opens up a dialogue on the uncanny and the circumstantial as Kennedy embarks on a conceptual journey highlighting the after-image, ghostly experiences and profane illuminations. His use of technology appears low key and the conceptual analysis is finely resolved in the form of the work.

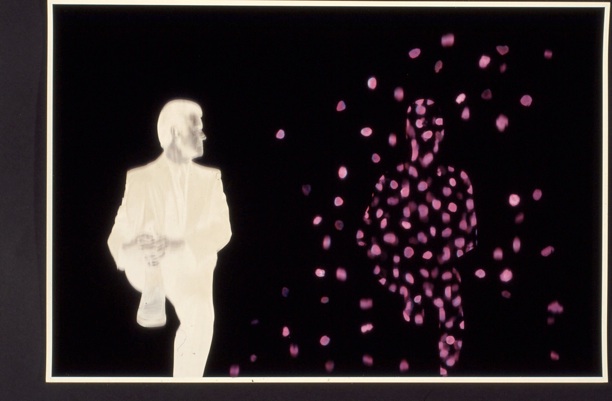

Peter Kennedy, My Ghost – and my own worst enemy (my cancer cells), no. 2, 2000-2002.

Pigment inkjet print. Digital compositing by Les Walkling

Photographs by Sandy Edwards

123.9 x 184.8 cm.

Peter Kennedy, My Ghost – and my own worst enemy (my cancer cells), no. 2, 2000-2002.

Pigment inkjet print. Digital compositing by Les Walkling

Photographs by Sandy Edwards

123.9 x 184.8 cm.

One of the central elements in Requiem for Ghosts is a wall of 'keywords' written in neon light with the centre of each word forming a dark space. Words and ideals are again cast in a position of fading but the technique of 'light writing' creates its own philosophical ambiguities. The vivid blue neon produces a negative space around the body of each word so that the word becomes object. The neon also has the effect of creating words of light which cast ghostly shadows, they are, in my mind, a meditation on 'light writing' and death, the kind of ideas that inspired the early photographers as well as generations of critics and philosophers who have explored the oppositions light and dark, positive and negative. In Requiem Kennedy worries the photographic medium and takes it back to its source as light-writing. But these are not romantic sun pictures where nature does the work, they are words made from neon, reminiscent of the street sign and city lights, the electrical buzz of modern life.

Seven people who died the same day I was born - April 18 1945 (Part 1)

In Requiem Kennedy uses light to explore death, coincidence and uncanny synchronisation. A wall of blue and sepia-toned photographs titled Seven people who died the same day I was born - April 18 1945 (Part 1) presents a kind of living tomb for the dead with each portrait accompanied by blue neon tubes with text detailing the stories of the peoples' lives.

Passage - with a twist

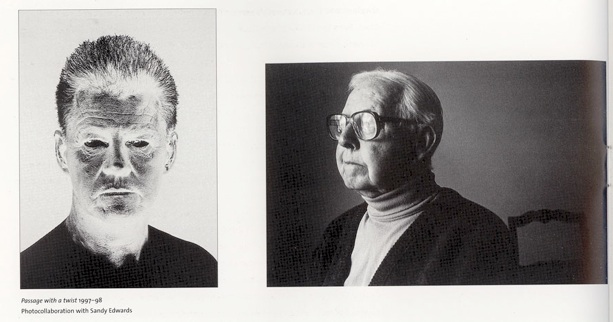

Peter Kennedy, Passage with a twist, 1997-8.

Photocollaboration with Sandy Edwards.

Peter Kennedy, Passage with a twist, 1997-8.

Photocollaboration with Sandy Edwards.

In this series, and the photo-triptych Passage - with a twist, Kennedy exploits the indexical nature of the photograph and its ghostly function. Writing about Walter Benjamin's reading of photography as allegory, Eduardo Cadava argues that:

In order for a photograph to be a photograph, it must become the tomb that writes, that harbours its own death. If the photograph is the allegory of our modernity, it is because, like allegory, it is defined by its relation to the corpse . . . the photograph dies in the photograph because only in this way can it be the uncanny tomb of our memory.12

Kennedy's exploration of the uncanny through photography is most literal in the biographical triptych Passage where he presents himself as a dark ghost hovering before a portrait of his elderly father who, having suffered memory loss after a series of strokes, has come to believe that his son is dead. The final image in the triptych is an enlarged snapshot of the artist as a boy in his father's arms. The self-portrait of the artist as a ghost, achieved by re-photographing the negative of a photograph of his face painted black, operates as a frightening spectre. Here, Kennedy anticipates his own death whilst creating a homage to his father whose capacity to remember his life is fading.

The Illuminated Steps - A War Memorial for the Twentieth Century

The Illuminated Steps - A War Memorial for the Twentieth Century is comprised of a glass shelf of anatomical x-rays, dead flowers and texts on death which represents the body as frail and skeleton-like. Its bones laid out in an illuminated, coffin-like box, scattered with quotations from T.S. Eliot, Wilfred Owen, Benjamin Britten, and the coral score of Missa pro Defunctis, and juxtaposed with a stretched photograph of the Milky Way.

People who were born the day I was born - April 18, 1945 (Part 1)

People who were born the day I was born - April 18, 1945 is an arrangement of black neon tubes with the birth notices from newspaper of the same day. Producing type-set text on the lights, Kennedy creates electric tombs which have the appearance of futuristic time capsules.

People who died the day I was born - April 18, 1945 (Part 2)

Peter Kennedy, People who were born the day I was born – April 18, 1945 (part 2), 1997-98.

White fluorescent light with text mounted on metal battens fixed to wall.

50 x 3600 x 75 mm.

Peter Kennedy, People who were born the day I was born – April 18, 1945 (part 2), 1997-98.

White fluorescent light with text mounted on metal battens fixed to wall.

50 x 3600 x 75 mm.

These occur again in People who died the day I was born - April 18, 1945 (Part 2) with the addition of blue neon script with words such as 'shot', 'suicided', 'died in hospital', 'executed', 'murdered', highlighting the final drama of each life. Kennedy calls the light capsules "taxonomies of life and death" and says that the text can be scanned "like channel surfing, like the way we receive most of our ideas about the world...in bits and pieces".13

Requiem uses light and dark to speak about death and its after-image. It is a lucid constellation of ideas that sets up a series of conceptual trajectories for the viewer. On one hand the big ideas of this century are written in neon, emblazoned in light. But they are also in a position of fading. Dark, negative spaces come into being at the same time that the light creates a ghosting effect throughout the gallery, leaving its after-image on the walls, ceiling and floor.

There are several themes, recurring motifs and ideas that are brought together in the work of the last decade to make up a constellation of artworks that relate to one another as well as to the spectator. Light (neon) and writing are brought together in stories that are accompanied by pictures. Photo-graphy (light-writing) is exploited for its indexical qualities.14 Kennedy uses the metaphor of the ghost and photographic ghosting to represent history and death. His use of the portrait and his re-configuration of press photographs underlines the idea of the photograph as an index. The ghosting and archival effects are made real by Les Walkling who has collaborated with Kennedy on the recent photographic works.

Meditating on the philosophy of history in 1940, Walter Benjamin turned to a small picture by Paul Klee titled, Angelus novus (1920), and he described the figure as the angel of history caught by the catastrophe of modern progress. This passage has since become one of the most quoted allegories from Benjamin s opus and it is a leitmotif that recurs throughout Peter Kennedy’s work. Of Klee’s angel Benjamin said:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay. . . But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”15

One long catastrophe

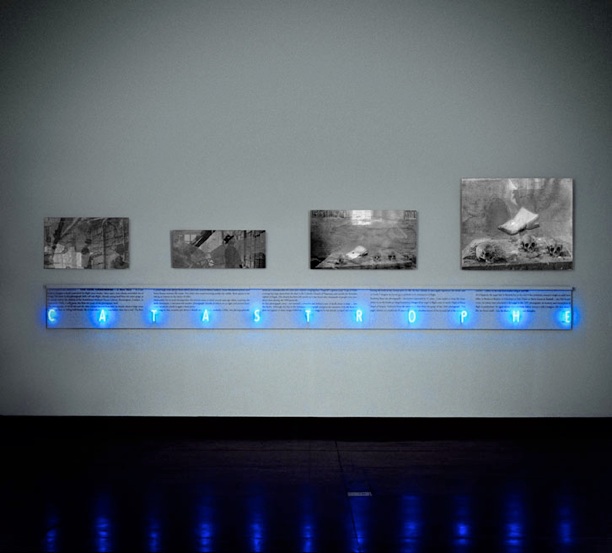

In Peter Kennedy’s photographic installation One long catastrophe (2000-02) we see this abstracted angel of history in four photographic images that have been digitally cropped and re-composed. Kennedy says he has always imagined the potential of the open book to take flight because it reminds him of wings.

Peter Kennedy, One Long Catastrophe, 2000-2002, installation view, the Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2002.

Pigment inkjet prints, neon, MDF. Digital compositing by Les Walkling.

Prints (left to right as installed): 69.3 x 112.5 cm, 52.8 x 126.4 cm, 80.7 x 144.2 cm, 127 x 154.4 cm; overall 212 x 707.5 cm approx. Photographs courtesy of Associated Press and English Heritage – National Monuments Record.

Peter Kennedy, One Long Catastrophe, 2000-2002, installation view, the Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2002.

Pigment inkjet prints, neon, MDF. Digital compositing by Les Walkling.

Prints (left to right as installed): 69.3 x 112.5 cm, 52.8 x 126.4 cm, 80.7 x 144.2 cm, 127 x 154.4 cm; overall 212 x 707.5 cm approx. Photographs courtesy of Associated Press and English Heritage – National Monuments Record.

In the two images on the left-hand side, we see a man perusing an open book in the bomblitzed Holland House Library in 1940. The original photograph has been reversed and we are presented with close-ups of three men who are using the library as they ordinarily would (I show one detail here). They seem totally oblivious to the ruined structure of the building.

Two details

On the right we see two digitally altered images of a 1997 news photograph of a small boy in Rwanda. In the original photograph, he crouches behind a row of skulls about to leap from the altar of a Catholic Church which had been abandoned after thousands of people were murdered there during the 1994 genocide. There is a large open book, probably a bible, spread open on the altar and the boy s image is now shown digitally transformed into a ghostly after-image, suggesting that he has already jumped and vanished leaving the book as the central actor. Les Walkling’s digital compositing reconfigures the photographs and gives them an archival quality by creating a stain effect that washes over the images.

The Holland House Library, Unknown Photographer

The Holland House Library, Unknown Photographer

The Holland House Library has become a famous image within the history of photography. Photographed by an ‘unknown photographer’, it captures an image of a reading culture, still finding pleasure in knowledge, amidst the debris of a violent war. The men are absorbed in the books as they become part of history. Eduardo Cadava used this photograph to illustrate his book Words of Light,16 a text which examines Benjamin’s use of photography as a metaphor for history. Peter Kennedy uses the photograph in a related way by creating a visual narrative that charts the allegorical journey of the open book (the angel of history) through time, to arrive, exhausted, in the present. Kennedy says:

Studying these two photographs documents separated by 60 years I am unable to resist the temptation to see the books as winged presences. Images of an angel in flight come to mind. Flight of fancy. Angel of history... This angel, witness to a multitude of catastrophes the relentless storms of the second half of the twentieth century suffers in the end from feather fatigue and falls. As it happens, the angel falls in Rwanda but at the end of the twentieth century it might as easily have fallen in Bosnia or Kosovo or Chechnya or East Timor or Sierra Leone or Australia no. No? In any event, no matter how exhausted is the angel in the 1997 photograph, its recovery and resumption of flight is predestined. Yet again driven uncontrollably before storms it will, I imagine, fall once more like the future itself into the shadow cast by my own thoughts.17

Angels and ghosts are recurring motifs throughout Kennedy s work where they are used as metaphors for history and memory. Kennedy seems seduced by the play of presence and absence, life and death.

At the end of the twentieth century - Comedy and Tragedy step out

Kennedy has always been an artist who has resisted and interrogated dominant political paradigms, however, in the 1990s and 2000s his visual language became much more poetic. Talking about the development of a poetic aesthetic in an interview in 1996, Peter Kennedy said:

I have had an abiding belief that an artwork’s capacity to resonate in the minds of an audience is very much contingent on its poetic presence. It is the power of this tenebrous emissary, hovering just beyond the immediately understood or directly knowable - this shadow-breath on our minds that invests the poetic with its resonating power”.18

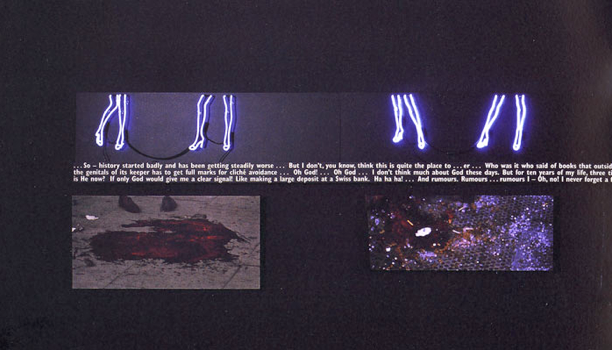

Peter Kennedy, At the end of the twentieth century – Comedy and Tragedy step out, 2000-2002.

Pigment inkjet prints, neon, MDF.

Digital compositing by Les Walkling.

Jokes (with apologies): Woody Allen, Russell Davies, Amanda Lear, Groucho Marx, Ronald Searle/Geoffrey Williams, Tom Stoppard.

Prints (left to right as installed): 56.6 x 115 cm, 46.5 x 115 cm, 65.5 x 115 cm, 70.6 x 115 cm; overall 530 x 636 cm approx.

Peter Kennedy, At the end of the twentieth century – Comedy and Tragedy step out, 2000-2002.

Pigment inkjet prints, neon, MDF.

Digital compositing by Les Walkling.

Jokes (with apologies): Woody Allen, Russell Davies, Amanda Lear, Groucho Marx, Ronald Searle/Geoffrey Williams, Tom Stoppard.

Prints (left to right as installed): 56.6 x 115 cm, 46.5 x 115 cm, 65.5 x 115 cm, 70.6 x 115 cm; overall 530 x 636 cm approx.

There is a sense of great tragedy in some of Kennedy’s work; however, there is often a sense of humour running through the installations., uses the extemporaneous language of a comedian to usher us into an abrasive relationship with the work s tragic aspects. There is a redemptive aspect to this work as tragedy and comedy , which are usually separated, interact in the installation. Running horizontally above the jokes, eight pairs of women s legs, rendered in vivid blue neon light, represent the two muses, beneath the jokes four press photographs, which have been enhanced through digital processing, show pools of blood split in conflict and war. In part the joke sequence reads:

...So history started badly and has been getting steadily worse... But I don’t, you know, think this is quite the place to... er... Who was it who said of books that outside of a dog a book is man’s best friend inside of a dog it’s too dark to read?...

The blue neon legs of the two muses are seen stepping out of the twentieth century, perhaps signifying a decadent Western culture where the body of woman is commodified. The muses are juxtaposed with a comedian’s skit on history, a script they may have written themselves. Beneath them, bloodstains represent the real. At the end of the twentieth century - Comedy and Tragedy step out has its genesis in Requiem: Choruses from the north and south. Both works, one predictive, the other reflective, can be seen in relation to the catastrophe of September 11 when terrorists from an impoverished region attacked the centre of economic power in New York. At the end of the twentieth century is accompanied by NOWANDTHEN Thursday 27 February, 1997 (1997-98), a work dealing with the Port Arthur massacre in Tasmania, and One long catastrophe, described above.

NOWANDTHEN is a neon light-writing and photo-documentary work that is presented as a conceptual word and image loop. It was originally commissioned by the Tasmanian Art Gallery and Museum. Kennedy was invited to create a new work with reference to the gallery/museum collection. The art gallery has a fine collection and the museum charts a troubled history, incorporating evidence of the conditions that the first convicts encountered within the prison garrison. NOWANDTHEN begins with the neon statement: and then now when the past isn’t what it used to be . The neon writing reads from left to right. Running horizontally under the words, neon arrows, heading right to left, urge the viewer to read the photographs beneath. The light prompts us to read quickly, and we are sped through history from the past into the present. These pointers are the mark of the broad arrow branding iron which was a standard symbol used to identify the property of the penal settlement, including the clothing worn by the convicts. The Broad Arrow Caf, which catered for tourists visiting Port Arthur, was the site of the massacre in 1996. In Kennedy s installation, the arrows serve as signs that propel the past into the future. Writing about this work Kennedy said that the past is:

& wrenched, unbelievably, from its chronological moorings and put to violent flight - its trajectory renting the present with such ferocity that both past and present appear to collapse inwardly into an abyss, a NOWANDTHEN time...”19

The photographic sequence shows convict clothing and the mark of the branding iron that appears to be hurled from the past and threatens to wound the present. The then present (now our recent past) is depicted in the newspaper photographs of the mayhem of the massacre as paramedics tend to the injured and the dying. The photographs for this sequence are taken from the museum s collection and the 1996 news reports of the event. The pictures transgress histories and resonate in the spectator s mind as the collision between past and present is made explicit in terms of our own recent history.

Kennedy is a fine draftsman, a complex thinker and an experienced collaborator who has worked with other artists throughout his career to realise some of his major works. Peter Kennedy tells compelling and disturbing stories about his own life and the events that have stained our collective histories. The way in which the artist creates his stories is visually dynamic and multi-layered. The work is rich with metaphor, humour and critique and it brings history, philosophy, politics and poetry together in the here and now. We might say that for Peter Kennedy, who works across so many media, the medium so prized by Rosalind Krauss is in fact a ghost.

Notes

1. Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea : Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Thames and Hudson, London 1991.

2. Rosalind Krauss, . . . And Then Turn Away? An Essay on James Coleman , October, no 81, 1997, p5.

3. See Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea and Reinventing the Medium , Critical Inquiry, winter 1999, pp. 289-305. Also Hal Foster, Design and Crime and Other Diatribes, Verso, London and New York 2002.

4. Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p48.

5. Rosalind Krauss, . . . And Then Turn Away?, p5.

6. Hal Foster, The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays in Postmodern Culture, Bay Press, Seattle and Washington 1983, pxii.

7. Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p6-7.

8. Rosalind Krauss, Sculpture in the Expanded Field in Hal Foster (ed.) The Anti-Aesthetic, pp31-42.

9. Walter Benjamin, 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction', p. 218.

10. Walter Benjamin, 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction', pp. 234-35.

11. Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcade Project, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991, pp. 274-275 (first published in 1989).

12. Eduardo Cadava, Words of Light, pp. 10-11.

13. Peter Kennedy as quoted by Louise Bellamy, 'In the end was the word', The Age, Saturday 21 February, 1998, Arts Extra, p. 5.

14. Susan Sontag was the first critic to analyse the indexical qualities of photography. She argued that photography was not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask. See On Photography, Penguin, Middlesex, 1979, p. 154 (first published in 1977).

15. Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1969, p. 249.

16. See Eduardo Cadava, Words of Light: Thesis on the Photography of History, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1997.

17. Artist s statement explaining the photographic sequence.

18. Interview with the artist (insert date)

19. Artist s statement, 15 Oct. 1998.

© 2025 professor ANNE MARSH | SITE BY jamie charles schulz